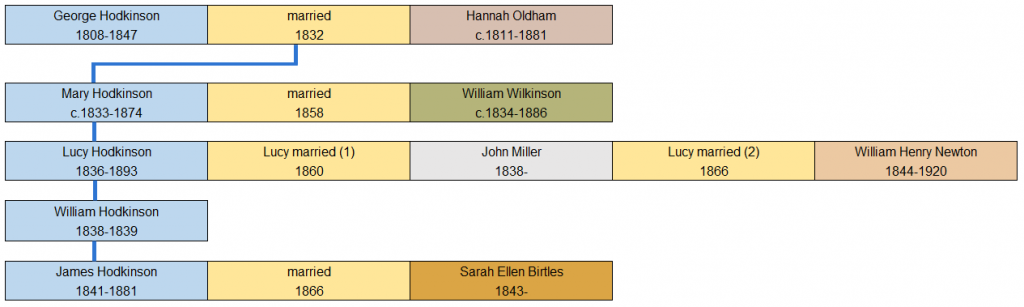

Lucy Hodkinson: 1836 to 1893

This page has a little about Lucy's baptism, but is mainly about her life from her first marriage in 1860 to her death.

Lucy Hodkinson's life before 1860 is to be found as follows:

- the story of Lucy Hodkinson from her birth up to 1841 is here; and

- the story of Lucy from 1841 to about 1860 is on the webpage which covers the shared history of Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson.

Lucy Hodkinson

- Born: about 1836

- 1st marriage: Monday, 6th February 1860 (age about 24). No children

- 2nd marriage: Sunday, 23rd December 1866 (age about 30)

- Six children: all boys

- Died: Thursday, 13th April 1893 (age about 57 years)

Lucy Hodkinson's birth, baptism and immediate family

Lucy Hodkinson's baptism on Sunday, 31st July 1836

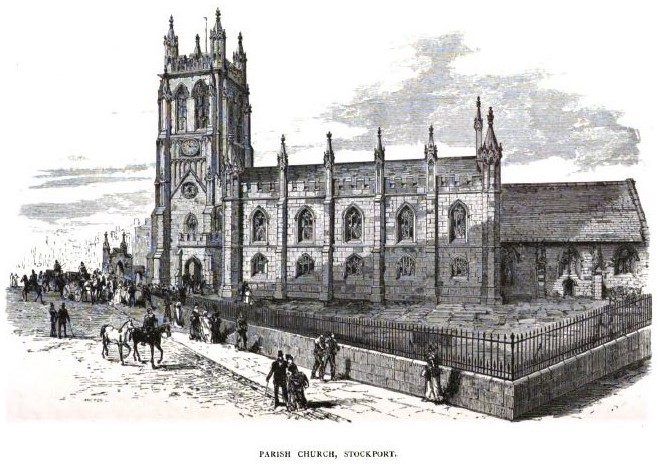

George and Hannah Hodkinson's second child, Lucy, was baptised on Sunday, 31st July 1836, in the parish church of St Mary in Stockport with her place of residence given as Rowcroft Smithy, which was on the outskirts of Stockport. There is no actual recorded date for her birth, but other records indicate she was born in 1836. Her place of birth is also unknown, but it probably was either Cheadle or Stockport. The baptismal record states her dad's occupation as "Spinner".

Taking the Hillgate route, the walk from the Hodkinsons’ home in Rowcroft Smithy to St Mary’s is about a mile. About halfway along is St Thomas' Church, Hillgate, the construction of which was completed eleven years before Lucy was born. Like St Mary's, it is Anglican and, for the Hodkinsons, would have been a more conveniently located place of worship. That being so, you can imagine the conversation between parents Hannah and George as they walked past St Thomas'.

Hannah grumbled. "I wish we went to church services at St Thomas’ and Lucy could’ve been baptised there and we wouldn’t have to walk so far."

George's reply was to the point. "Hannah, I’ve said so many times that St Mary’s is our church. I was baptised there and I want Lucy baptised there as well."

Hannah was having none of that and threw in a bit of history. "But it’s not the same church. It’s a new church. The old church got knocked down. You got baptised in a church that isn’t there anymore."

"It is there. It’s in the same place. It’s still St Mary’s. Some of the old church is part of the new church."

Hannah wasn't going let go of her grumble. "I don't care if some of the old church is part of the new church. It’s so far to walk. It's really hilly when we get near the church. It’s not fair on me and the children. It’s tiring carrying Lucy. And look at Mary. She’s tired of walking. She’s three and she’s got to walk so far. We should have gone to St Thomas’. Stockport is so hilly. It was much better when we lived in Cheadle."

When the family arrived at St Mary's, it was Rector Charles Kendrick Prescot who conducted the ceremony. He was fifty years old and had been in post since 1820 and would remain so until 1875.

The first image is of St Mary’s Church in Stockport2, the baptismal place of Lucy Hodkinson. Her dad George was also baptised in 1809 in St Mary’s. However, the church itself was demolished in 1810 to make way for a newer version, as seen above in an 1880 engraving. Henry Heginbotham, in his 1882 history of Stockport, was clear he didn’t like the replacement, commenting “Little can be said in favour of its architectural pretension, as it is immensely inferior to the ancient structure in design and appearance.”3 The second image is of Rector Charles Kendrick Prescot4 who baptised Lucy. He held his rectorship from 1820-1875, having succeeded his father who had been in the post since 1783. Between them, father and son held the position of rector for ninety-two continuous years. Quite an achievement!

Lucy Hodkinson's parents and siblings

The first marriage of Lucy Hodkinson, in February 1860, to John Miller

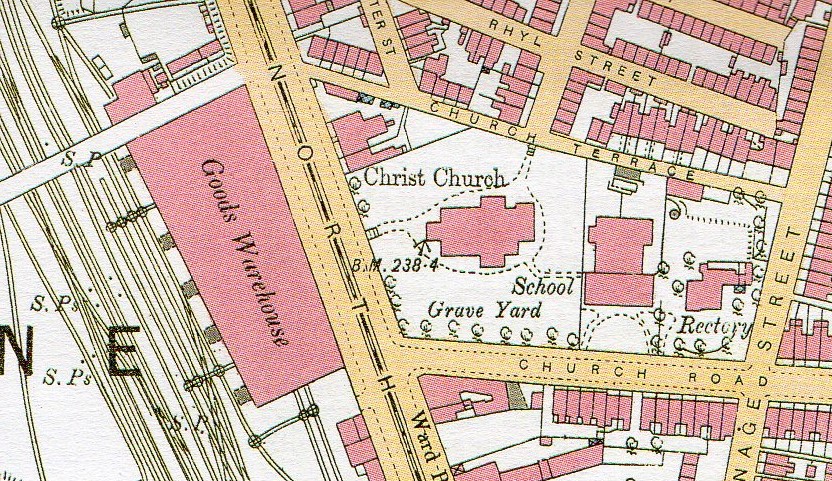

Lucy Hodkinson and John Miller's wedding venue: Christ Church, Heaton Norris, Stockport

This is Christ Church in Heaton Norris, Stockport, the place of marriage of Lucy Hodkinson and her first husband, John Miller. A Cheshire Gazetteer from 1860 comments that "Christ Church, an elegant edifice of freestone, stands in a conspicuous situation on the east side of Wellington-road North, in Heaton Norris. It is a cruciform structure in the early English style, surmounted by a lofty and well-proportioned spire 180 feet high, which is furnished with a clock having three dials. The internal arrangements have a very chaste and elegant appearance, and there is accommodation for 1,230 worshippers ..."5 With the building experiencing fire, vandalism and theft in the late 20th century, all that is left is the tower and some of the walls of the aisles, with no access to the remains. Click on an image above for a larger version. The map has a re-surveyed and a revised date of 1892-1893 and is reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. (Photographs: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Lucy Hodkinson's wedding: a look at the seven names on the marriage certificate

John Miller: groom

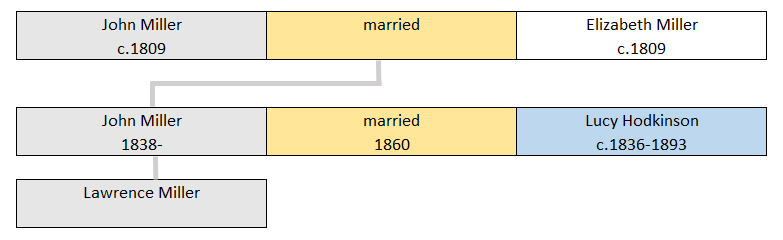

John Miller was born in Stockport in April 1838, the first child of John Miller and Elizabeth Miller who were both born around 1809. When John Miller junior married, he was 22 years old.

As far as I can see, there are only five original sources which definitely relate to John Miller. They are, in chronological order: his birth certificate of 1838; a church record of his baptism in 1838; the census returns for 1841 and 1851; and his marriage certificate of 1860. There is also a somewhat inaccurate entry in the 1861 census which very likely relates to "our" John Miller. At that point, the identifiable paper trail dries up. With John Miller’s life after 1861 being a mystery, so too is exactly where he was living at the time of his marriage. The marriage certificate does not give the actual addresses of John Miller and Lucy Hodkinson simply stating the name of the parish: “Christ Church, Heaton Norris”.

Still, we know that John Miller’s occupation, at the time of marriage, was a wheelwright and also that he was – to some extent – literate. Unlike bride Lucy, John Miller signed his own name on the marriage certificate. The signature looks laboured and lacks flow, but John’s ability to write, and therefore read at even an elementary level, meant that there was a guarantee that the Hodkinson surname would be spelt correctly on the marriage certificate.

I’ve spent virtually no time in researching John Miller’s ancestry, as can be seen from the tree above. However, I have spent a lot of time in trying to find out where and when he died, but to no avail. I keep trying, from time to time, and when I feel I may have found the right John Miller in death records, I order a copy of his death certificate, and, invariably, it is the wrong John Miller. Still, I now have a decent collection of a range of John Miller death certificates!

John Miller: groom's father

As mentioned previously, father John Miller and mother Elizabeth Miller were both born around 1809. Elizabeth Miller was already a Miller at birth. The marriage certificate states John Miller was a labourer; at least one census return is more precise in saying that his occupation was an agricultural labourer.

Lucy Hodkinson: bride

Lucy Hodkinson’s date of birth is not known, but her death certificate of 12th April 1893 gives her age as 53 years, which would mean she was born in 1840. However, this information is wrong. Census returns indicate that she was born in 1836, the same year that she was baptised. She was, therefore, 24 years old when she married.

As noted above, the marriage certificate gives no actual address for Lucy’s home. If she was living in Christ Church Parish in Heaton Norris, then she was no longer living at the family home at 44 Ratcliffe Street, Hillgate, about a mile away.

No occupation is given for Lucy, but that does not mean she was not working – often church marriage registers did not record such information for females.

William Hodkinson: named as the bride’s father

Lucy’s marriage certificate states that William Hodkinson was her father; in fact, he was her step-father. It is easy to understand why she did this. Her natural father was George Hodkinson who left the family home when Lucy was five, after the affair between his wife, Hannah, and their lodger, William Hodkinson, became known.

Effectively, Lucy knew no other father except William and so declared him as such on the marriage certificate. Sadly, neither father nor step-father was alive to see their second (step-) child get married – natural father George Hodkinson died in 1847 and step-father William Hodkinson died in 1858.

Winter trees blend in harmoniously with the remains of Christ Church, while the railings complement the spire and pinnacles, all pointing heavenwards. This view is the back of Christ Church, taken from what was once Church Terrace. (See map above.) (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

William and Emily Lamb: witnesses

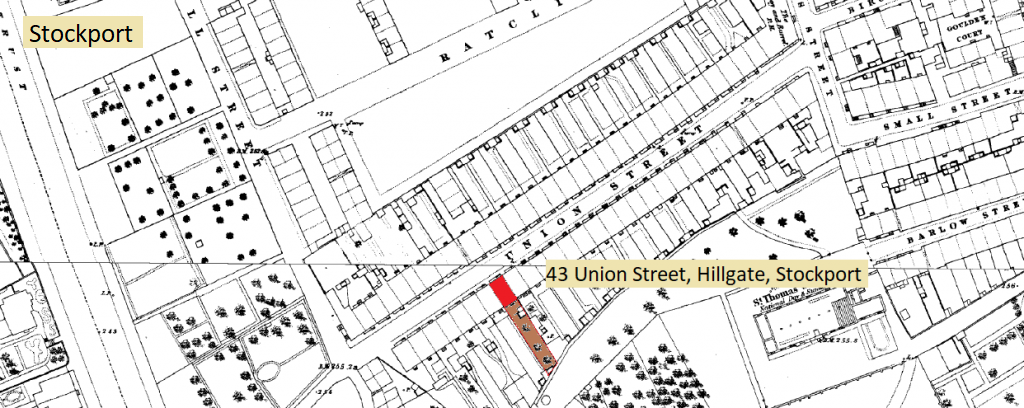

The two witnesses, William Lamb and Emily Holt, married in 1858. Two years later, when John Miller and Lucy Hodkinson married, William Lamb was about 30 and Emily Holt about 28. The 1861 census states that they lived on Bamford Street, Stockport, which ran parallel to the three streets where the Hodkinson family lived during the 1840s to the 1860s: Mottram Street, Ratcliffe Street and Union Street. The last street was also where Lucy was living as a lodger in 1861.

C.B. Jeaffreson: Rector

Charles Babington Jeaffreson (he must have found misspellings of his surname quite irksome!) officiated at Lucy Hodkinson's wedding. He was born in 1819 in Islington, studied at Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he was awarded a B.A. degree in 1842 and a M.A. degree in 1844, and became the first rector of Christ Church in 1846. He was a wealthy individual and the 1861 census gives an indication of his lifestyle in the rectory, listing his wife, five children and three servants – a housemaid, a cook, and a nurse who presumably cared for the youngest child/children in the family. It was quite a contrast to the abject poverty experienced by so many of his parishioners.

Charles Babington Jeaffreson remained in post until he died in 1877 at the age of 58. He had spent 31 years as rector – an indication of how much he loved his parish and his church. It was fitting that he was buried in the church’s graveyard – not that he would have been interred elsewhere!

The 1861 census with a focus on Lucy Miller (Hodkinson)

Census returns provide a snapshot of people’s circumstances on one day in every ten years, but even a small amount of information can give a fascinating insight into personal lives. This is the case with Lucy Hodkinson who, in 1861, was Lucy Miller and who would become Lucy Newton in 1866.

Lucy’s marriage to John Miller was fourteen months old in April 1861, but they were living apart. Lucy was a lodger, at 43 Union Street, Hillgate, Stockport, a house inhabited by two families: John and Mary Burrows and their stepson; and Edward Towers, Emma Towers and their son, who lived in the cellar. Additionally, there was another lodger, Jemma Haworth. It is puzzling to understand why Lucy should live in a household with seven others when four of her siblings and her mother lived two streets away. Had she fallen out with her mother? Moreover, her father-in-law and her brother-in-law (but not her husband) were living at 26 Longshut Lane, not that far from Lucy’s home, which does raise the question that if Lucy didn’t want to stay in her mother’s home, then why not stay in her father-in-law’s house?

The 1861 census shows he already had a lodger; Lucy would have taken the household occupancy to only four, much preferable to her accommodation in Union Street.

It took some time to find Lucy’s husband in the census returns. However, making due allowances for a census transcription error and a misspelling of the Miller surname, it looks probable that he was living as a lodger in Stalybridge and working as a cotton weaver.

There could be many reasons why Lucy chose to live independently from her immediate family and her in-laws. The reason why her husband was living in Stalybridge may well have been because he found better employment opportunities there, rather than in Stockport whose economy had stagnated for many years.

In 1861, Lucy Miller (Hodkinson) was living as a lodger at 43 Union Street, Hillgate, Stockport. This OS map (an extract from an Alan Godfrey Edition) was surveyed in 1849 – when there was still some land which hadn't been swallowed up by industry and housing – and published in 1851.

Yet there was something not quite right with Lucy’s first marriage. If John moved to Stalybridge because the opportunities for work were good, then Lucy could have joined him. Moreover, birth records show that the married couple had no children which may or may not be significant in terms of the couple’s relationship. Lucy Miller remarried in 1866 which means that John Miller died at some point between 1861 and 1866. Unfortunately, trying to find a date and place for John Miller’s death, substantiated by a copy of his death certificate, has been unsuccessful. There are family trees on genealogy sites which have information about John Miller, but they all have errors, including details of when and where he died. If those details were known, then they would shed light on the length of the marriage, where he was living at the time of death and whether or not it was Lucy who reported the death.

Lucy’s second husband was William Henry Newton, who was a few days short of being 17 years old at the time of the 1861 census. He, like Lucy Miller and John Miller, was also not living with his family. His father was deceased and his mother was living in Old Gardens, Stockport, with two daughters, two grandchildren and a lodger.

William Henry Newton appears as Henry Newton, age 15, in the 1861 census, living in a house in the aptly named Newton Street in Stockport. The head of the household was Joshua Reid who would have been responsible for providing the census details, including William Henry’s incorrect age. Further, since William Henry Newton’s first name is not stated in the census, it looks as though Joshua knew William Henry as Henry, so that may well have been his preferred name.

Joshua Reid’s occupation is given as a “shopkeeper and Farmer of 10 acres, employing 1 boy”. It is quite an occupation description for a census return and probably reflects some kind of status insecurity. Still, it is a snippet of valuable information. In the census (William) Henry is stated to be a servant in the household and his occupation is given as an agricultural labourer. It is probable that William Henry was a labourer for Joshua Reid (the “1 boy”) by day and a servant for the same person at other times.

At some point, Lucy and William Henry met each other and a relationship developed which led to marriage.

The second marriage of Lucy Hodkinson, in December 1866, to William Henry Newton

Just before the marriage: Lucy Hodkinson, as was, and her immediate Hodkinson family

As the excitement of her second marriage approached on Sunday, 23rd December 1866, Lucy Hodkinson may well have taken stock of her life so far. She had lived through five deaths in the Hodkinson family: her father, her step-father, her first full-brother, and her first and second half-sisters. Her husband by her first marriage, John Miller, was also deceased. As regards those still alive, her mother, Hannah Hodkinson (Oldham), was, it would appear, still living in Stockport in the long-term family home at 44 Ratcliffe Street.

It is likely that two of Lucy’s half-brothers were living with Hannah Hodkinson – William Hodkinson who was sixteen and John Hodkinson who was fourteen. Lucy’s full-sister, Mary Hodkinson, was about 33 years old, married to William Wilkinson and living in Birkenhead. Her full-brother, James Hodkinson, was 25, living in Ashton-under-Lyne and about to get married to Sarah Ellen Birtles. Half-brother Samuel Hodkinson was a private in the 39th Regiment of Foot and currently stationed in Chester.

At face value, Lucy’s second marriage certificate, like her first, provides basic, solid and reliable information about seven people but research shows that this was not the case with all those named on the certificate.

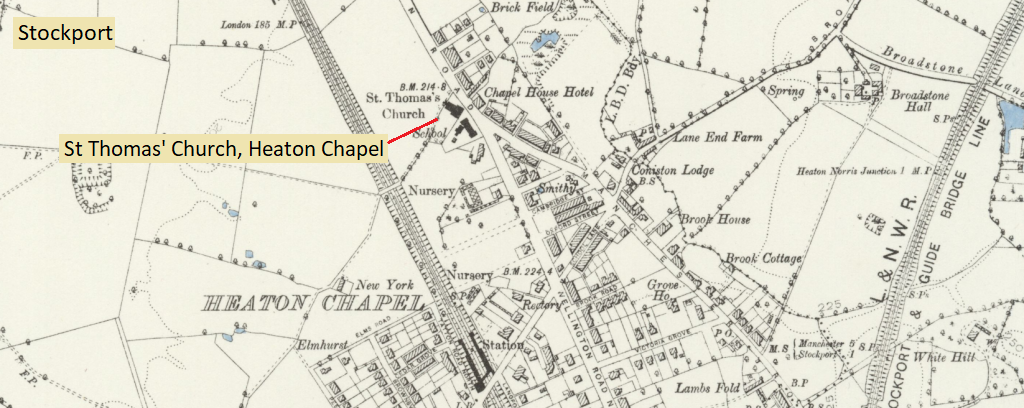

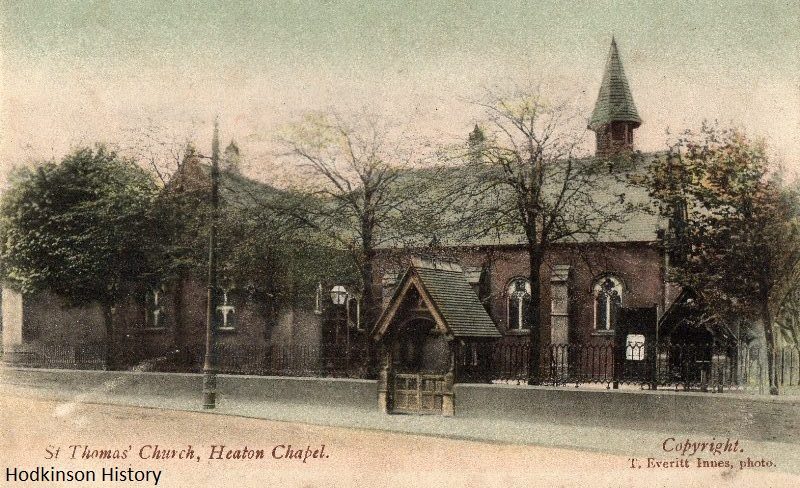

Lucy Miller (formerly Hodkinson) and William Henry Newton's wedding at St Thomas the Apostle, Heaton Chapel, Stockport

The map above was surveyed in 1889-1892 and published in 1894 and is reproduced with permission from the National Library of Scotland. St Thomas' Church in Heaton Chapel is where Lucy Hodkinson, as was, married for a second time.

St Thomas' Church in Heaton Chapel, the place of marriage for Lucy Miller (nee Hodkinson) and William Henry Newton, underwent a great deal of building work, both interior and exterior, a few years after Lucy's marriage. The church in the image above, therefore, is different in appearance from the church where Lucy Hodkinson married. It was also very different from the Gothic Revival splendour of Christ Church, where her first marriage took place. (Postcard: property of Samuel Hodkinson.

St Thomas' Church, now lacking any exterior charm it may have had, is near the busy junction of Wellington Road North and Manchester Road. It took a bit of time waiting for a gap in the heavy traffic before this deceptively quiet view of the church could be taken. (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

William Henry Newton

The entries on the marriage certificate state William Henry’s age as 21, his occupation as “Labourer” and his residence as “Heaton Norris”.

William Henry Newton was born in April 1844 which meant he was 22 at his wedding. However, the stated age of 21 on the marriage certificate was merely to signify that he was 21 or older. Anyone marrying under the age of 21 needed the approval of their parents who could forbid the banns of marriage if they were not happy with their child’s marriage intentions. Likewise, Lucy Miller (Hodkinson) was stated to be age 21 on the marriage certificate, whereas she was actually 30, eight years older than her husband.

As regards William Henry Newton’s residence at the time of marriage, “Heaton Norris” as an entry on the marriage certificate is, unfortunately, very limited. When William Henry and Lucy’s first child was born, his address was in Water Street, Heaton Norris. Maybe this was where William Henry and Lucy lived following their marriage.

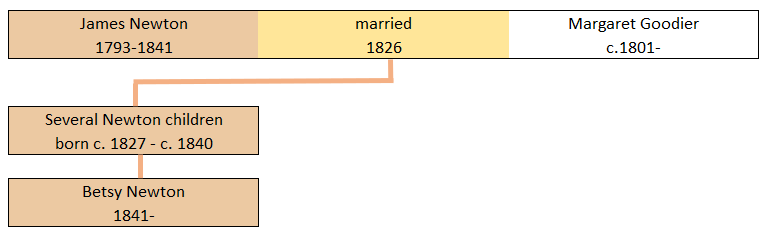

James Newton: named as the father of the groom

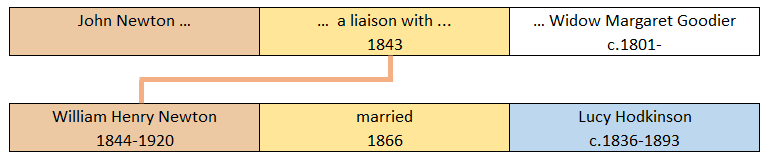

William Henry’s mother was Margaret Goodier, born around 1801; she was the second wife of James Newton, born in 1793, and married him in 1826.

James Newton is named as the father of William Henry on the marriage certificate and most Newton trees on various genealogy sites appear to have used that piece of information in constructing the family tree of William Henry. However, William Henry was born in 1844, but James Newton died in 1841, three years earlier. In November 1841, widow Margaret Newton gave birth to Betsy Newton; the child's birth certificate states the father as "James Newton (deceased)".

William Henry’s own 1844 birth certificate states his mother is Margaret Newton (Goodier) and his father is John Newton. However, there are no marriage records for Margaret Goodier and John Newton and Margaret’s marital status is “widow” in the 1851 census. Fortunately, with both parents having the same surname, William Henry was born as a Newton and so avoided the stigma that was attached to being illegitimate.

It may be that William Henry was never told by his mother who his real father was, which may explain why he said his father was James at the marriage ceremony and why his first child with Lucy was named James Newton, rather than John Newton. But, who was John Newton? A number of Newton family trees on genealogy sites show that James Newton had a brother called John Newton who was married with children. Could he have had a secret liaison with his sister-in-law that led to the birth of William Henry Newton? Or was John someone completely different? Answering that question is a nice little research project for someone.

As for James Newton, the best match in terms of a death certificate is one from April 1841 for a James Newton who died in the Stockport workhouse, age 56. There is a discrepancy here with James' actual age of 48 in that year, but such inconsistencies were not uncommon in workhouse records.

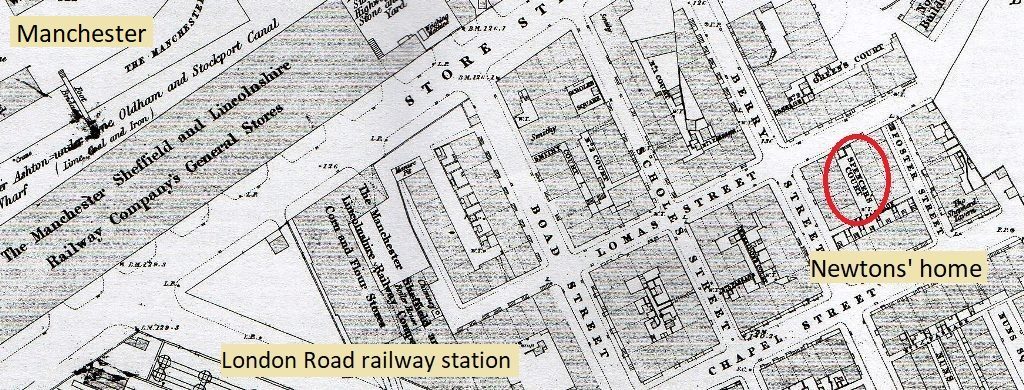

William Henry Newton and his family tree

The family relationships that weren’t – William Henry Newton’s marriage certificate would place him firmly within the above abbreviated family tree, but the reality was that his dad was not James Newton, as above, but John Newton, as below. There are a lot of more detailed and comprehensive family trees on various genealogy sites for various Newton families, but they do vary in quality.

Lucy Miller (nee Hodkinson): bride

As mentioned earlier, Lucy Hodkinson was born in 1836 and so was 30 when she married her second husband. The marriage certificate gives no actual address for Lucy’s home, simply stating "Heaton Norris". Additionally, no occupation is stated, but that does not mean she was unemployed – it simply indicates that, as a female, her occupation was not that important to be recorded.

William Hodkinson: named as the bride’s father

Both William Henry and Lucy had incorrect names for their fathers on the marriage certificate. As mentioned earlier, Lucy was five when her natural father, George, left the family home and she effectively knew no other father than her step-father, William Hodkinson.

James Hodkinson and Sarah Eliza Birtles: witnesses

James Hodkinson (1841-1881) was Lucy's brother. Two days after Lucy's marriage, James married Sarah Eliza Birtles in Ashton-under-Lyne. One of the witnesses to James' wedding was William Henry Newton. More information about James Hodkinson's marriage can be found here.

E D Jackson: Rector

Edward Dudley Jackson was 63 when he officiated at Lucy Hodkinson’s second wedding ceremony. Born in 1803 in Warminster, he gained a first-class honours degree in Law from Trinity Hall, Cambridge in 1827 and became Rector of St Thomas’ in 1843. It appears the Reverend Edward Jackson was not without private means – for example, he contributed £200 towards the cost, upwards of £1,200, of building the parsonage, completed in 1847.

The Reverend also appears to have had the personality to grow his congregation, to the extent that St Thomas’ church provided an extra 160 seating spaces in the early 1850s. He enjoyed writing and his varied output included The Crucifixion and other Poems; Scripture History; and a Grammar School Atlas.

Edward Dudley Jackson stayed in post for the next 35 years, only leaving in 1878 due to ill health. He died the following year.

Lucy's age embarrassment?

Based on census returns and her baptismal record, Lucy Hodkinson was born in 1836, probably in the first few months of the year.

She was eight years older than William Henry Newton, but that difference was covered up. The marriage certificate simply states that she was over 21, but what is interesting is that the next time her age was recorded was in April 1870 on board the barque Indus, taking her to Australia, when she stated her age to be 27, although she was 34. Even when she died, her age was recorded as 53 rather than her true age of 57. When she met William Henry, did she lie about her age, and keep the lie going for the rest of her life, because she was embarrassed about being older? Did William Henry know her real age, maybe shared her embarrassment, and was complicit in her lies?

Lucy Newton (Hodkinson) and her family on the move

Better employment and/or a better standard of housing were worth moving for, and, with that in mind, the Newtons moved from Heaton Norris, Stockport to the central area of Manchester and from there to Birkenhead. Unfortunately, these locations provided nothing better in their lives and so the Newtons decided to go much further, to one of Britain’s colonies on the other side of the world – Queensland, Australia.

After marriage, Lucy had six children with the first two being born in England and the following four being born in Australia. It was not unusual for parents to baptise their children with the same first name, although from research carried out for this website, it appears that Hodkinson family first names were more likely to be "re-used" following the death of a younger sibling.

Heaton Norris, Stockport

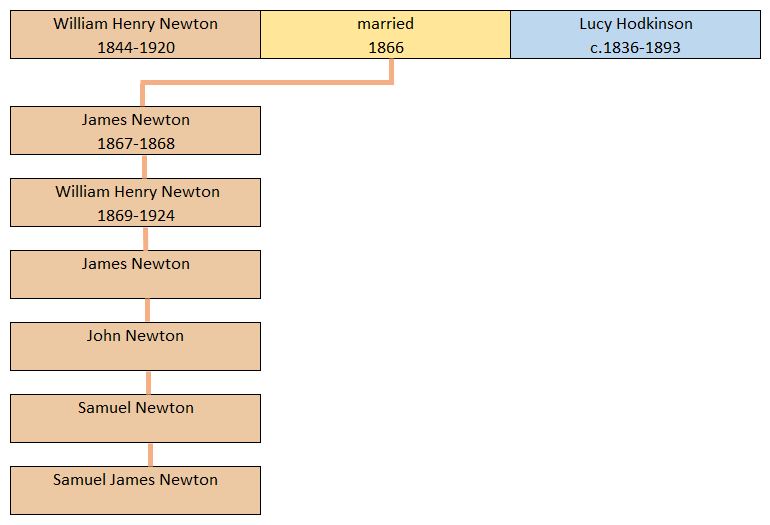

The Newtons' first son – James Newton – was born at 95 Water Street, Heaton Norris, Stockport. The Newtons may have moved to this address after their marriage.

The map above (an extract from an Alan Godfrey Edition) was surveyed in 1849 and revised in 1873. In September 1867, Lucy Newton (Hodkinson) and her family were living at 95 Water Street, Heaton Norris, Stockport where their first son, James Newton, was born. Water Street was renamed Bridgefield Street; most of its route still exists. However, all the housing has gone, replaced, over time, by commercial and business premises and car parks.

The first photograph shows the junction of Heaton Lane (on the left) and Wellington Road North. Mersey Square is to the right of the image. The entrance to Bridgefield Street, formerly Water Street, is marked on the photograph, the view being roughly from where the long arrow is on the map. As can be seen, the Hodkinsons' home at 95 Water Street was just a short walk away from Wellington Road North. On top of the cream-cladded building is a car park and the second photograph is taken from there (shown by a short arrow on the map), showing the present-day Bridgefield Street. (Photographs: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Manchester

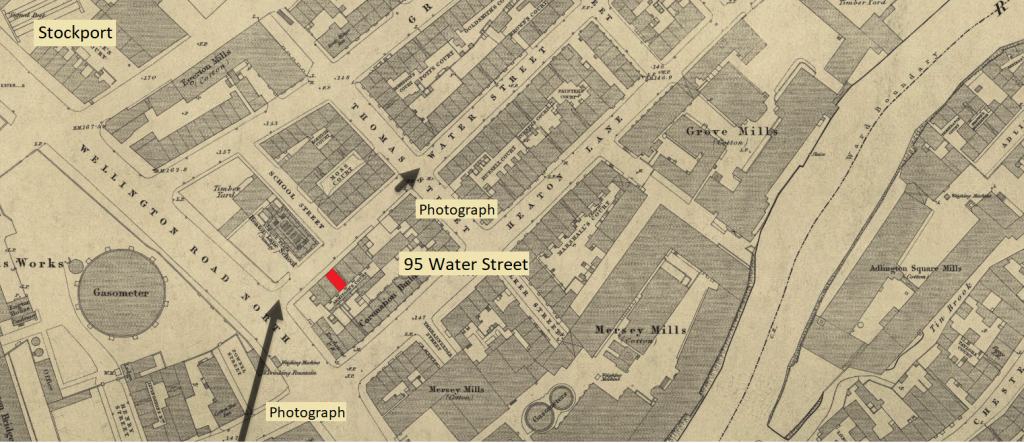

A year later, the Newtons could be found at Spencer's Court, Manchester, as shown on the map below. This was where James Newton died, five days before his first birthday.

In 1868, Lucy Newton (Hodkinson) and her family were living at 7, Spencer's Court, Manchester. This is where their first son, James Newton, died. How long the Newtons lived at this address is not known. The OS map (an extract from an Alan Godfrey Edition) was surveyed in 1849 and published in 1851. London Road railway Station is now Manchester Piccadilly.

The image above is looking towards Lomas Street, as on the map above. If you were to walk by the side of the wall of the flats that look out on Sparkle Street, from the left of the first balcony nearest the camera, to the right of the balcony at the other end of the building, then you would have walked down the middle of the length of Spencer's Court. Since I couldn't that, I walked along the pavement next to the hedge, and tried the impossible task of imagining Lucy Hodkinson's life in a slum in that tiny little bit of Manchester. (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Birkenhead

The Hodkinson family living at 44 Ratcliffe Street, Stockport, started to split up from the late 1850s, especially as the children grew up and left home. Lucy Newton's sister, Mary Wilkinson (Hodkinson), was living in Birkenhead by 1865 with the rest of her family. With the Newtons fed up with Manchester, why not join the Wilkinsons?

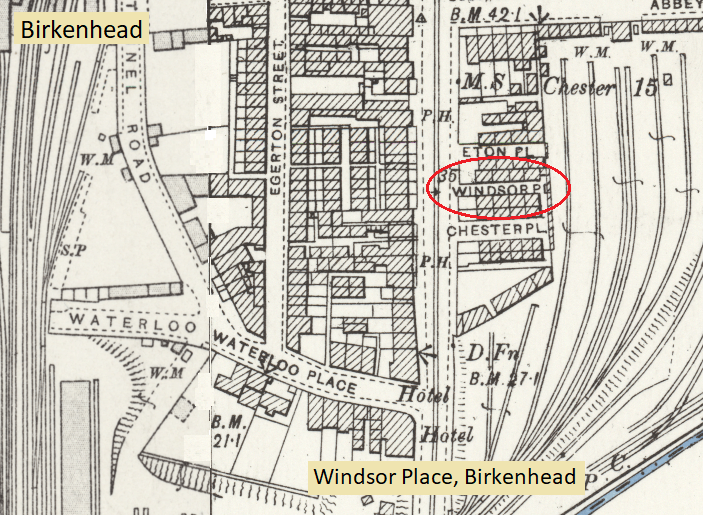

Join up they did, and the two families lived in the same house at 6, Windsor Place, Birkenhead for at least several months in 1869 and 1870. It was here that William Henry Newton was born in 1869 and where Alfred Wilkinson was born, and died, in 1870.

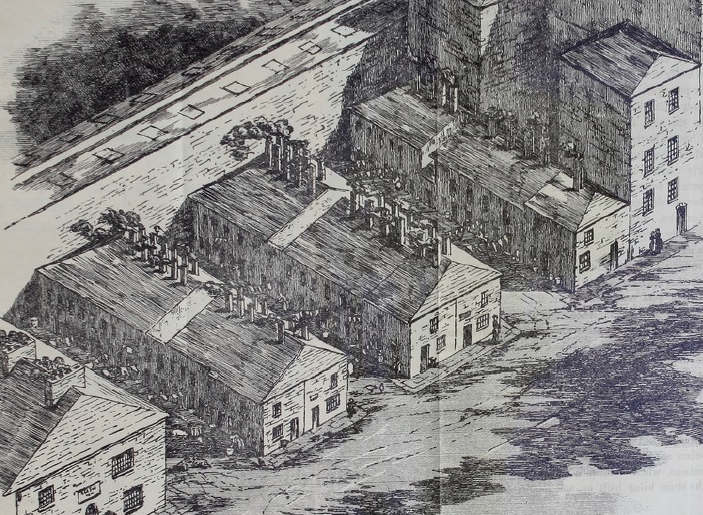

The home at 6 Windsor Place – just like their previous address at 7 Spencer's Court – was, unfortunately, at the lower end of working-class housing. Both homes were back-to-back houses, in dirty, unhygienic and densely populated areas, with heavy industry and extensive railway operations contributing to noisy and polluting and bleak, dispiriting environments. By about 1869, the Newtons had had enough and made their momentous decision to emigrate, the result of which was that the family landed on Australian soil on 21st July 1870. It’s inconceivable that Mary Wilkinson and her family were not involved in the discussions about emigrating – it’s a shame that the reasons why they didn’t also emigrate will never be known.

Birkenhead had its own Windsor and Eton – and Lucy Newton (Hodkinson) lived in one of those places. The house at 6, Windsor Place, Birkenhead, was a slum, a back-to-back house shared for a number of months in 1869 to 1870 by two Hodkinson sisters – Lucy Newton and Mary Wilkinson, and their respective families. The illustration is from 1854, depicting back-to-back houses in Manchester, the type of housing that all members of the Hodkinson family were familiar with. The map, published with permission of the National Library of Scotland, has a revised date of 1898 and a publication date of 1899.

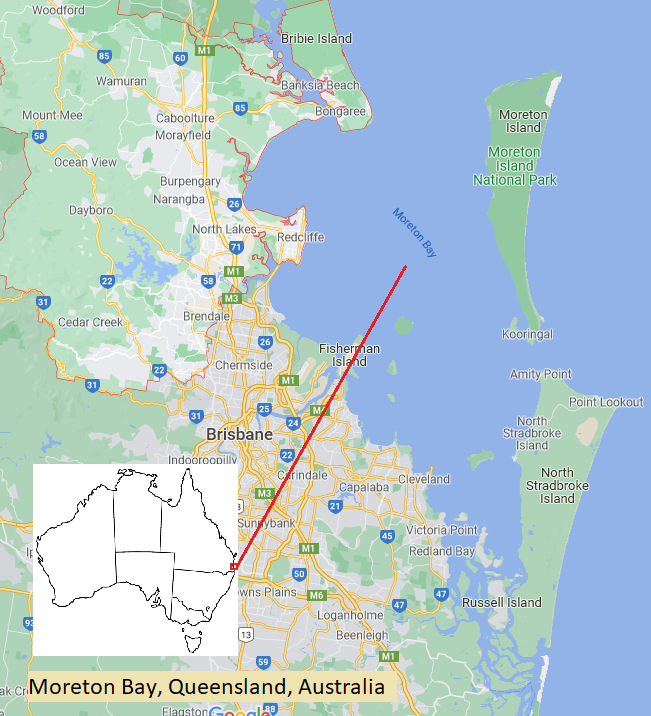

1870: from Birkenhead to Moreton Bay, Queensland in 106 days

One hundred and six arduous, tiring and sometimes frightening days and nights lay ahead for the Newtons when they left Birkenhead on Thursday, 7th April 1870, at the start of their journey to Queensland.

Thursday was spent getting to Gravesend, which is about 21 miles east of central London, to join their ship. They travelled by train, perhaps to Liverpool first, from where they could take a direct service to London Euston, followed by more travel to Gravesend. An overnight stay in or around the town meant that they had some rest before they boarded the barque Indus on Friday, 8th April 1870. A tugboat towed the Indus from the dock towards open seas and then it was left to wind power and sails to take the ship to Queensland. There is no doubt that the Newtons felt excited at what lay ahead, despite knowing that they would spend many, many weeks in cramped and restrictive surroundings.

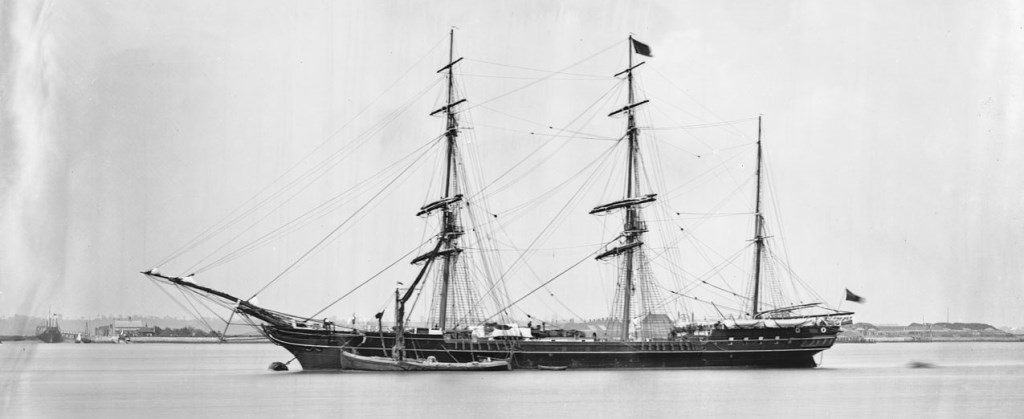

This is the ship that took the Newtons to a fresh start in Queensland. The image, of the barque Indus (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London), is from a glass plate negative made in April 1871. A barque is a ship with at least three masts. The museum's accompanying description states the view is of a “slightly distant port near broadside view, taken from just ahead of the beam, of the 3 masted barque rigged vessel Indus (built 1847) at moorings in Gravesend Reach, River Thames. She is rigged with double topsails, single topgallants and royals. A stumpy rigged spritsail barge is alongside forward. The Coast Guard Watch Vessel CGWV 28 (1847) is on the Tilbury shore in the left background.” (Image reproduced with permission of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.)6

The ship’s register lists 479 passengers, including 88 children who were 12 years or younger. There were 24 saloon passengers (equivalent to first class), 20 second cabin passengers (second class) and the rest numbered 435 and travelled in steerage which was the poorest accommodation available on ships and was located below the main deck. It is no surprise that William Henry Newton, Lucy Newton and their child William Henry Newton, were steerage passengers and, along with another 145, had the cost of the journey paid for by the Queensland Government.

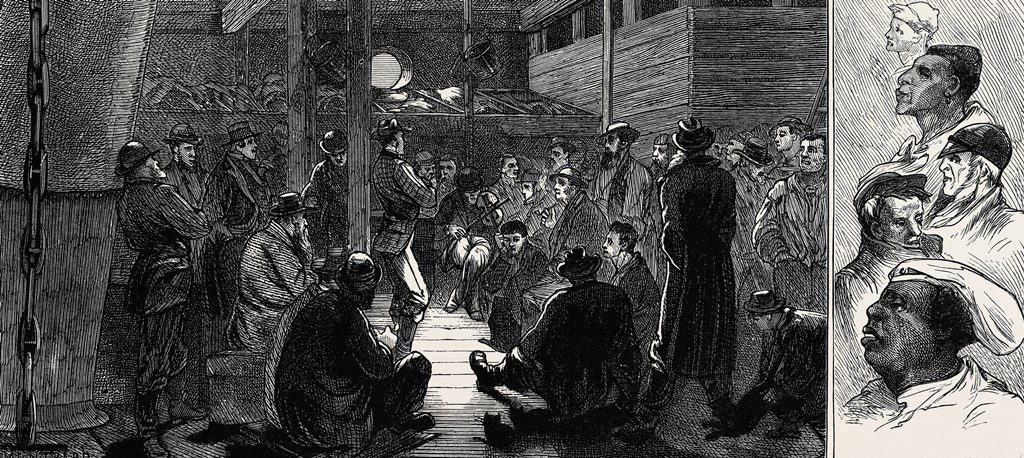

Another passenger travelling for free was George Newton, age 21. He was born in Bedfordshire and was not related to William Henry Newton and family. Within steerage, there was a separate area for single males. (See illustration below.)

How many adult passengers did William Henry and Lucy Newton talk to during 105 days at sea? Was George Newton one of them?

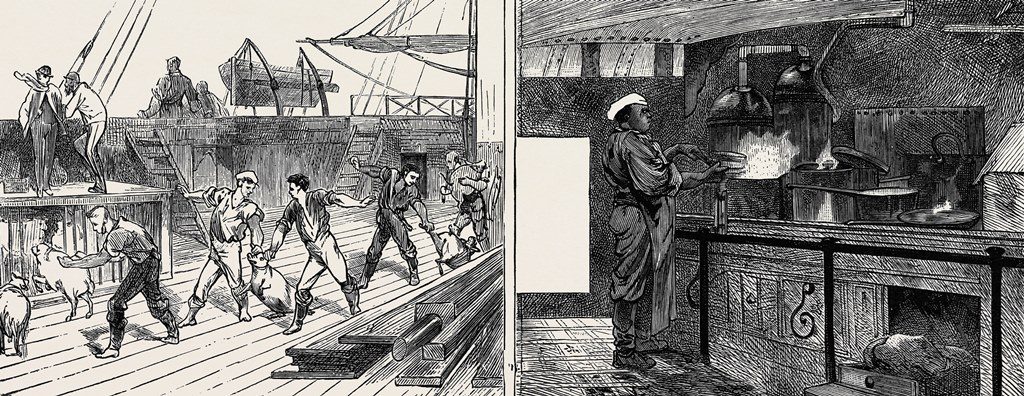

Two years after the Newtons travelled to Queensland, an artist visited the Indus before its departure for another journey to Queensland and provided the weekly newspaper The Graphic7 with drawings of life on board, scenes which would have been very familiar to the Newtons. The image above, on the left, is of the area in steerage where single men, such as George Newton, had their accommodation. Note the bunk beds. The images on the right are of five crew members who may well have been on the ship in 1870 when the Newtons were passengers. The man at the top appears to the same person as the man helping to move a pig in the deck drawing below. The chef is also depicted in the drawing of the ship's galley, below.

Before boarding and in line with standard practice, the Newtons were grouped together with about five to seven others to form a mess, one of dozens created with the intention that emigrants cooked, ate, washed and cleaned within their own messes. Living conditions were bad, to say the least, yet the Newtons, like so many in steerage, were inured to such conditions – after all, living in unhygienic, cramped and overcrowded back-to-back houses in industrial cities and towns had accustomed them to hardship.

Other drawings of the Indus in 1872 depict aspects of life on board. Live pigs and other small animals were kept on the ship to provide fresh meat at different stages on the journey. Steerage passengers had to do their own cooking. The cook in the drawing would be providing meals for a better class of person!

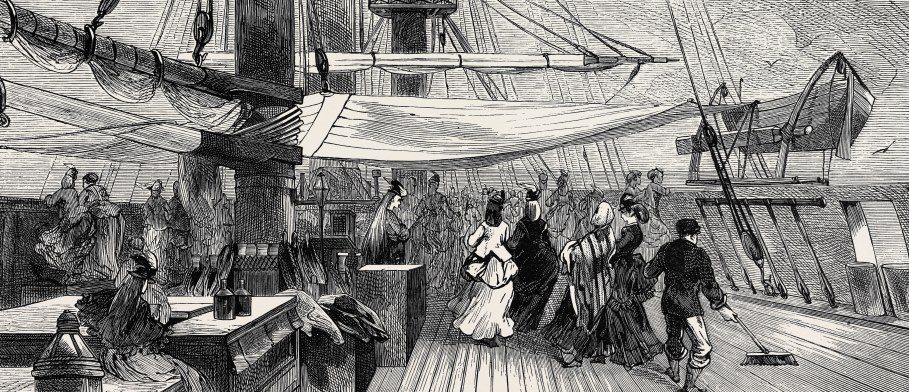

The newspaper caption for this drawing states, "The ladies on deck".

The ship finally arrived in Moreton Bay on Thursday, 21st July 1870. It lay at anchor in the bay whilst the passengers were ferried ashore in smaller craft. There were less passengers at the end of the journey than at the start, with four burials at sea taking place. There were also two births on board; in each case the child was given ‘Indus’ as a middle name.

Standing on Australian soil for the first time, the Newtons knew that the fresh start they had longed for was now a reality. They settled into their new country and, in due course, the Newton family had four more children, with the last birth taking place in December 1878.

The death of Lucy Newton (Hodkinson) in 1893

Lucy Newton died on 13th April 1893 in Bundaberg Hospital, Queensland. The reasons for death as stated on a death certificate are, out of necessity and for accuracy, uncompromising. So it was with Lucy's death certificate which gave the reason for her death as chronic syphilis, with her stay in hospital lasting 44 days. Her husband, William Henry Newton, remarried six weeks later. Bearing in mind the above, there is no doubt that the marriage of Lucy and William Henry was in tatters in early 1893, and probably had been for much longer. Who was initially responsible for this sad state of affairs is for conjecture, but one of the results in a chain of events was the death of Lucy Newton.

Lucy was the last of Hannah and George Hodkinson's four children to die. Her younger brother, William, died decades earlier, in 1839. Her sister Mary, to whom she was very close, died in 1874. Her older brother, James, died in 1881.

Apart from the few lines above, Lucy Newton's journey to Australia was the point at which I stopped my research into her life, much as it would have been fascinating to find out what happened after she and her family landed. Family trees on genealogy sites give more information about their descendants, of whom most appear to live in Queensland.

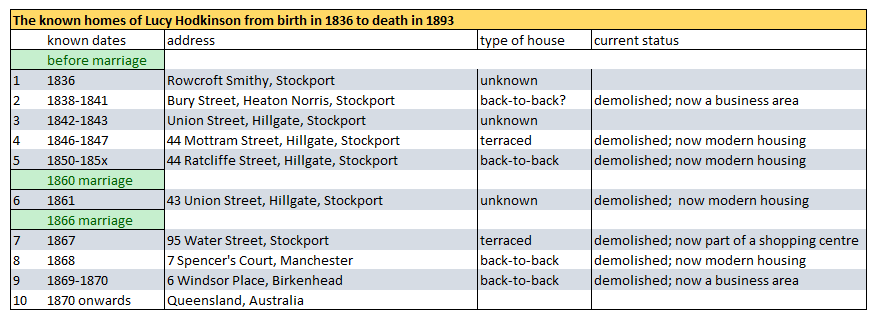

The homes in England of Lucy Hodkinson ... Miller ... Newton

The known dates for the homes in England where Lucy lived are stated below. She would have lived in some of these places for much longer than the date(s) given. Additionally, there is no doubt she also lived elsewhere, but the locations are unknown.

Details of her homes from 1836-1841 are here.

Details of her homes from 1841-1860 are here.

Details of her homes from 1860-1893 are further up this page.

In 1870, the Newton family moved to Australia. As mentioned previously, the arrival of the family in Queensland marks the end of my research on Lucy.

Notes and sources for this page:

- John Hatton, Lecture on the Sanitary Condition of Chorlton upon Medlock. (Manchester: Beresford and Galt. 1854.) pp. 8-9.

- Henry Heginbotham, Stockport: Ancient and Modern. (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. 1882.) Vol. I. Illustration between p.216 and p.217.

- Henry Heginbotham, Stockport: Ancient and Modern. (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. 1882.) Vol. I. p.217. (Is ibid out of fashion?)

- Henry Heginbotham, Stockport: Ancient and Modern. (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. 1882.) Vol. I. p.322.

- Francis White and Co., History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Cheshire. (Sheffield: Pawson and Brailsford. 1860.) p.790.

- Royal Museum Greenwich, Collections. Indus 1847. (https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-1051017. 21 March 2022.) ID G1763.

- Illustrated Newspapers Limited, The Graphic. (London: 29 June 1872.)

This page was originally published on 23rd March 2022 and with lots of updates made by 8th June 2023. Further updates were completed by 7th March 2025.