James Hodkinson: 1841 to 1881

The story of James Hodkinson’s life is on three separate pages.

Click here to read about James' birthplace and family in 1841, in Heaton Norris in Stockport.

Click here to read about his life from 1841 to his marriage in 1866, except for information about his baptism and education which is on the page you are currently reading.

On this page, there is information about his baptism and education, but the main emphasis is on his life from his marriage in 1866 to his death in 1881.

James Hodkinson1

- Born: Saturday, 27th March 1841

- Married: Tuesday, 25th December 1866 (age 25)

- Six children: three boys and three girls

- Died: Friday, 4th February 1881 (age 39 years and 10 months)

James Hodkinson's baptism and immediate family

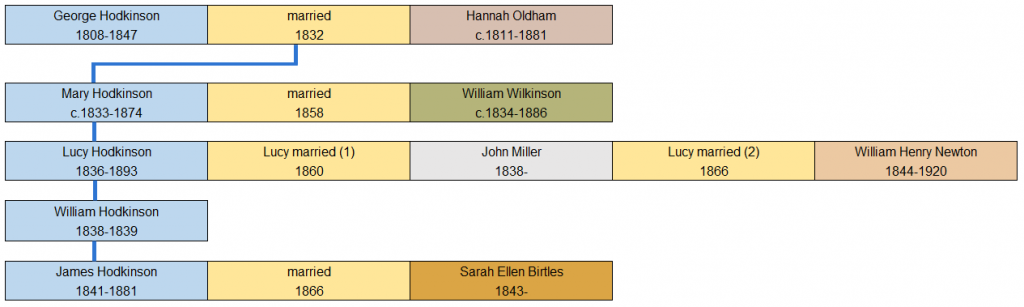

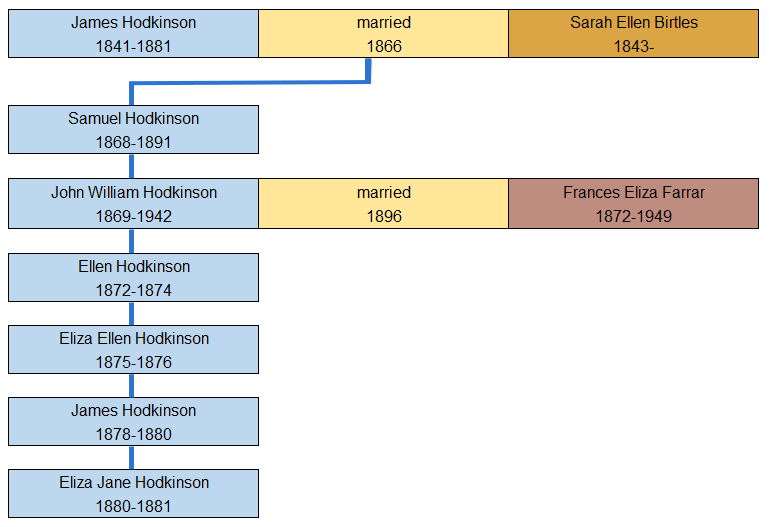

Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson can be seen in the extract below of the Hodkinson family tree, which has been repeated on some other webpages for clarity and convenience.

George and Hannah's third child, William, died when he was seven months old. There is more about him here.

James Hodkinson's baptism on Sunday, 16th January 1842 at St Thomas' Church, Hillgate, Stockport

On Sunday, 16th January 1842, the Hodkinsons, accompanied by godparents and other friends, made the short walk from their home on Union Street to the Parish Church of St Thomas for their son’s baptism.

St Thomas' was – and is – a magnificent church and, in 1842, was still more or less surrounded by open spaces. The clean exterior of the building would have darkened considerably after seventeen years of exposure to Stockport’s polluted atmosphere, but that wouldn’t have detracted from the superb nature of the venue for the christening.

The nature and requirements of the ceremony itself were stated unequivocally by an editor in an 1842 edition of The Christian Magazine (which according to one reader was extensively circulated in Stockport) and those comments continue to reflect, in general terms, baptismal ceremonies nowadays:

To be properly baptized a child should be taken to the Clergyman of the parish, to the Church, on some Sunday or Holy Day, with two Godfathers and one Godmother if a boy, with two Godmothers and one Godfather if a girl. The Clergyman will either sprinkle with water, or immerse the child if the parents require it, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost The child is thus baptised, and thereby regenerated, placed into covenant with God, and made an heir of everlasting salvation through Christ.

All parents, as they would have their children made Christians and heirs of heaven must have them baptized. We would very strongly recommend any of our readers who are not fully acquainted with the nature of the sacrament of baptism, to read the baptismal service in the prayer book very carefully, and besides this, to consult their parish priest upon the subject.2

The first photograph, a 2017 view of the interior of St Thomas', is one that James would recognise despite some changes in decor, fixtures and fittings. What he would find alarming would be the size of the congregation – often around 1,800 when he was alive, down to around 40 in the year when this photograph was taken. The second photograph is of the baptismal font, where James was baptised. (Photographs, with permission of the church: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Hannah Hodkinson and step-father-to-be William Hodkinson (and perhaps, but very unlikely, natural father George Hodkinson) had taken their time in arranging James' baptism. In her book, Daily Life in Victorian England, Sarah Mitchell comments that most children were christened at about one month of age,3 but this was not the case with the Hodkinson family, as with many other families. As an example, James was almost ten months old when his mother carried him to the baptismal font. Maybe Hannah Hodkinson's marital problems delayed a christening until she felt her life was more settled. Then again, it was at least eighteen months before her first child, Mary, was baptised when they lived in Cheadle.

It would have been cold inside the building for church heating in early Victorian Times was generally inadequate if non-existent, certainly for those who sat in the galleries; moreover, it was January and the building was cavernous. All participants in the baptismal ceremony would have been wrapped up well, but cold would have seeped through layers of clothing and the end of the ceremony may well have been a relief.

The education of James Hodkinson

Currently, there are no online records relating to any kind of education for James' sisters Mary and Lucy Hodkinson. Maybe they never attended any schools at all, including Sunday schools. That would not have been surprising in an age when the education of females was second place to educating males.

There are two brief records for James Hodkinson which shed some light on his time in two Stockport schools.

One record is his registration as a pupil at St Mary’s National School when the family was living in Ratcliffe Street. James’ father was stated to be William Hodkinson, reflecting not only the absence of his natural father (George), but also Hannah Hodkinson's desire to keep her marital history a private matter.

James' actual dates and pattern of attendance at St Mary's are not known. Also unknown is the quality of education at the school, but, in line with the curriculum that was found in National Schools at the time, reading and writing would have been taught even if it was to a rudimentary level.

The second record which mentions James 'Hodgkinson', with his father stated as William (actually his step-father), relates to Stockport Sunday School showing that James became a pupil in September 1847, at the age of six. Stockport Sunday School had thousands of pupils and James was assigned to class 42. He was 'discharged' in 1853, with non-attendance as the reason. His 'state of learning' was described as 'Reading Easy'.

James' schooling, such as it was, was of limited value. As an adult, James failed the test of basic writing skills when he signed his marriage certificate in 1866 with a cross. Nationally, the percentage of males unable to sign marriage certificates with their names had declined from 33% in 1840 to 20% in 18754, which placed James in a sizeable, but somewhat embarrassing, minority.

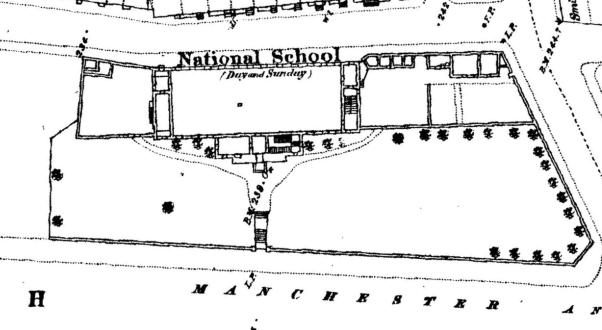

The first image is a detail from an Ordnance Survey Map of 1851, looking east. St Mary's National School, built in 1825–1826, was located in an area bounded by Edward Street, Lord Street, Eliza Street and Wellington Road South. The site is now occupied by Stockport Town Hall. James was a registered pupil at the school and the buildings in the second image present a view that James would have loved or loathed ... or perhaps neither if his school attendance was poor. The photograph and the map show the school facing Wellington Road South.

At the same time, James' ability to read must be called into question since the marriage certificate stated his surname as ‘Atkinson’, although his wife and the witnesses also appear not to have noticed, or could not read, this variation of the Hodkinson surname.

James' illiteracy does not mean that his mother and his stepfather-to-be placed no value on education. After all, he was registered at St Mary's and some of his half-siblings were also registered at Stockport Sunday School. Before the advent of free education, the stark reality for so many working-class Victorian families was a choice between either paying fees to send a child to school or sending a child to work so that the child's wage could be added to the household income to make life better – even marginally – for all the family. It was a choice between James Hodkinson being educated (rather than his sisters) and his family being able to pay the rent and/or experiencing hunger less often. It is not surprising, then, that James started working from an early age, just like his sisters and his half-brother, Samuel. Why bother with education?

On a mission? James Hodkinson heads to Ashton-under-Lyne from Stockport

In about 1866, James Hodkinson left Stockport most likely because it made employment sense – either for a job in its own right or for better paid work. Stockport had many industrial neighbours and so the question is why James chose to go to Ashton-under-Lyne. One reason was that Ashton-under-Lyne was more prosperous than Stockport. This was true of other towns, but James' choice was probably influenced by his wish to be in a town where many held the same religious beliefs as he did. Another reason which may have come into play – but unlikely – was that the overall standard of housing in Ashton-under-Lyne was better than that in Stockport.

Employment opportunities

From 1861–1865 the textile industry in the north-west of England was badly hit by the so-called Cotton Famine – a deep depression brought about by overproduction in a time of contracting world markets, the interruption of bailed cotton imports caused by the Civil War in America and by cotton being held in warehouses by speculators who were hoping for further rises in prices. Unemployment and short-time working was widespread. How the Hodkinsons were affected is unknown, but it is hard to believe that they did not escape unscathed. Ashton-under-Lyne suffered far more than Stockport, but recovered well and by 1866 its economy was in better shape than that in Stockport.

Within that context, James Hodkinson appears to have made the move from Stockport to Ashton-under-Lyne during the early part of 1866. By 1871, other members of his family were also living in the same town.

Religious solidarity

At some point in Stockport, James Hodkinson decided to eschew the Hodkinson Church of England tradition and joined the Methodist New Connexion (MNC). It seems that James preferred the principles of the MNC, aptly summarised in a MNC 1848 publication which stated:

These principles involve, representation of all interests, freedom of commerce, religious equality, voluntary support of religion, liberty of thought, enlightened piety, christian union, and strong solicitude for the welfare of the masses in humble life. 5

James would have faced much criticism from friends and perhaps some members of his family, but there would have been other friends who were already members of the MNC who would have discussed with James the tenets of the church and, above all, would have provided him with moral support.

When James decided to leave Stockport, Ashton-under-Lyne had something which other local towns with similar level of prosperity didn't have – a large MNC following. Importantly, one of the characteristics of the MNC was that it had a strong 'family feeling' and, if James joined the MNC in Stockport, then a deciding factor in moving to Ashton-under-Lyne was that he would be with like-minded people who would provide advice and/or help in finding accommodation and work.

Better housing

Two decades or so before James moved to Ashton-under-Lyne, Engels had been scathingly critical of housing conditions in Stockport, but found little to condemn in Ashton-under-Lyne.6 Despite that, poor living conditions were not uncommon in the town, something that James and his new family would experience with devastating consequences.

James Hodkinson at work in Ashton-under-Lyne

James Hodkinson: carder

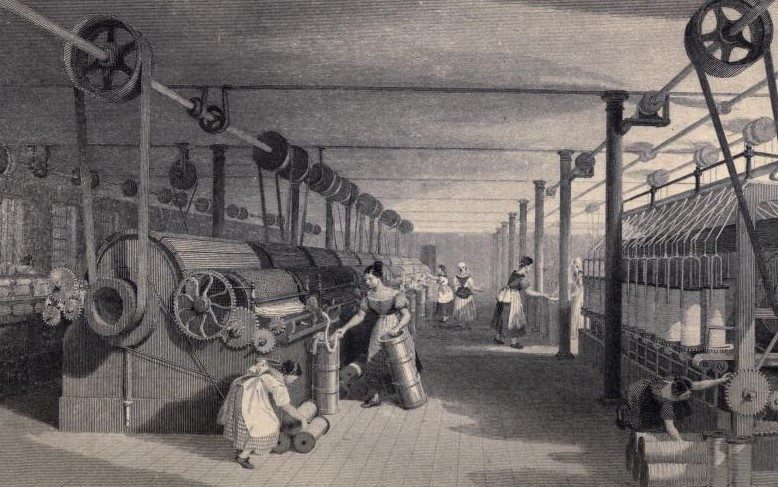

This oft-used 1840 illustration7 shows machines in the carding, drawing and roving room of a mill in Preston. The room appears spacious, helped by a high ceiling necessary for the height of the machines; the workers looked well-dressed; the work floor is not crowded; and the illustration gives the impression of a relaxed working environment. What images like this do not convey are the noise, the humidity, the dangerously dusty atmosphere, the boring long hours, the low wages with no job security, the hunger, the lack of sleep creating an overwhelming feeling of tiredness, the necessity of having to work when ill or heavily pregnant – and the list could be longer. James Hodkinson experienced so many of these: it is no wonder his health was badly affected, so much so that he did not reach the age of 40.

It seems unlikely that James would have moved to Ashton-under-Lyne without being reasonably certain that he would be able to find employment. Maybe there was a job waiting for him, arranged by his fellow MNC worshippers. James was familiar with the cotton industry, having worked as a piecer and then, as an adult, as a labourer in a cardroom. It is not surprising, then, that his December 1866 marriage certificate states his occupation to have been a cotton card stripper which was the kind of job that he held for the next eleven years or so, but not necessarily in the same factory.

The cards – the machines to separate fibres in cotton – were to be found in a cardroom, but this room would have had other machines which dealt with other aspects of the spinning process. As a 'card stripper', James had to carry out maintenance on the cards, which was a dirty, disagreeable and low-status job.

Like so many others, James kept an eye on what jobs were available elsewhere and took opportunities when they arose. Working in the damp and noisy environment of a cotton factory had its drawbacks, so he found more attractive sounding employment as an 'outdoor labourer'. However, James kept the job for only a short time.

Leaving that aside, James appears to have spent his working life until about 1878 in the textile industry. From that year, he is recorded as working in an iron foundry as a labourer. For James, the damp and warm conditions so necessary in a cotton factory for the successful spinning of thread were now replaced by the sharp and spiteful heat of a foundry.

James Hodkinson: iron foundry labourer

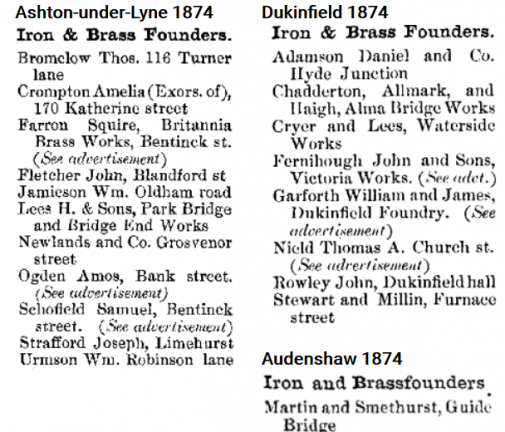

The lists of Iron and Brass founders in Ashton-under-Lyne, Dukinfield and Audenshaw have been taken from the Morris Trade Directory of 1874.8

James had at least four different homes in Ashton-under-Lyne. When he lived at 31 John Street, the nearest iron foundries to his home were:

- Newlands and Co., Grosvenor Street, Ashton-under-Lyne; and

- Martin and Smethurst, Guide Bridge, Audenshaw.

When James moved to 25 Whittington Court, the nearest iron foundries were:

- Amos Ogden, Bank Street, Ashton-under-Lyne;

- Samuel Schofield, Bentinck Street, Ashton-under-Lyne; and

- Cryer and Lees, Waterside Works, Dukinfield.

Bearing in mind that workers often lived near to their place of work, maybe – just maybe – James worked at one of these foundries. Interesting enough, James' second son, John William Hodkinson, would also work in the iron industry. Unlike his father, John William would eventually have a skilled job, as a core maker, with a corresponding job status that his father never had. James did not live long enough to see that happen, but he would have been proud that the only one of his six children to live beyond the age of 23 was able to move up the social scale.

The 1866 marriage of James Hodkinson and Sarah Ellen Birtles

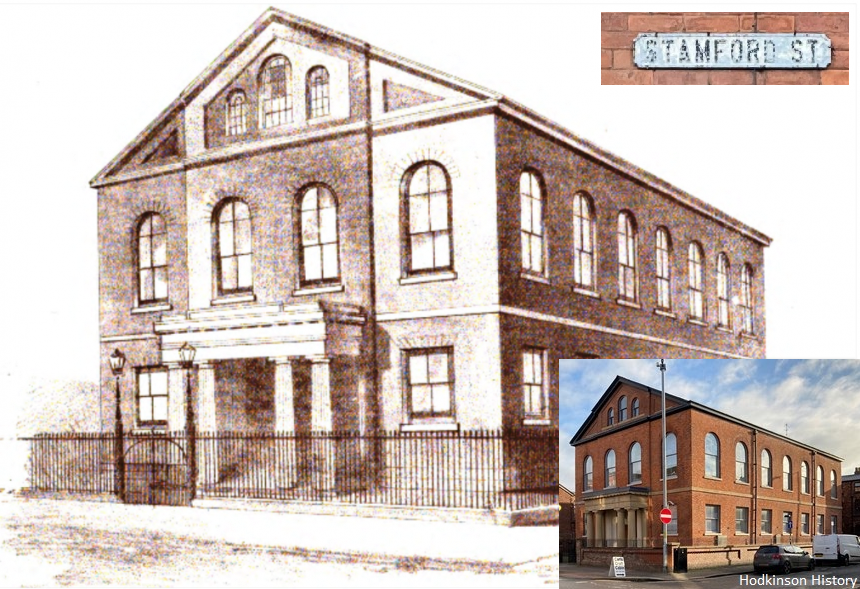

Once settled in Ashton-under-Lyne, with somewhere to live and somewhere to work, James started to meet people and make friends. One of those friendships developed and, in 1866, The Methodist New Connexion (MNC) Chapel on Stamford Street in Ashton-under-Lyne was the venue for the wedding of 25-year-old James Hodkinson and 23-year-old Mancunian Sarah Ellen Birtles.

The day of the week was a Tuesday but what made the ceremony extra special was that this particular Tuesday was Christmas Day. The marriage would have taken place early in the day, as was standard practice at the time.

The wedding was important not only in its own right, but it also marked the depth of James Hodkinson's commitment to the MNC. However, whatever family and friends thought of James joining the MNC, the two individuals who witnessed the signing of the marriage certificate were members of the Church of England. They were William Henry Newton, James' brother-in-law, and Ann Clayton.

In 1866 James Hodkinson and Sarah Ellen Birtles walked through the portico of the New Connexion Chapel on Stamford Street to enter the building for their marriage. This illustration is from an 1884 history of Ashton-under-Lyne.9 The building dates from 1799, with the premises being enlarged in 1832 providing seating for 900 worshippers. In 1842, Edwin Butterworth wrote, "The New Connexion Methodists are a large body and have flourished in this district for many years. The spacious and neat chapel of this society is in Stamford-street and was originally commenced in 1799. The edifice has received several decorations of late years."10 Stamford Street chapel still stands. The small photograph shows the chapel having undergone its own conversion, from a derelict religious building to a secular one containing apartments.

Who was who – eight people named on the marriage certificate

James Hodkinson: groom

On the marriage certificate, James' surname is given as "Atkinson". It is a shame that his attendance at school was virtually non-existent and that he didn't at least learn to read and write his name, otherwise he may well have spotted the error. James' age is stated to be 26, whereas his actual age was 25 years and eight months. His "rank or profession" is given as "Cotton card stripper". His address – Church Street, Ashton-under-Lyne – was probably number 185, where his first two children would be born.

George Hodkinson: the groom’s father

George Hodkinson ("Atkinson" says the wedding certificate) was James’ father, but James would have had no memory of his dad who left the family home when he was about one, after the affair between his wife, Hannah, and their lodger, William Hodkinson, became known. George Hodkinson died in 1847 and step-father William Hodkinson died in 1858.

Sarah Ellen Birtles: bride

On the marriage certificate, Sarah Ellen's age is given as 22. She is a spinster, working as a power loom cotton weaver and living on Princess Street, Hurst.

James Birtles: the bride's father

James is stated as to be deceased (he died in 1851) and his occupation is recorded as being an engraver.

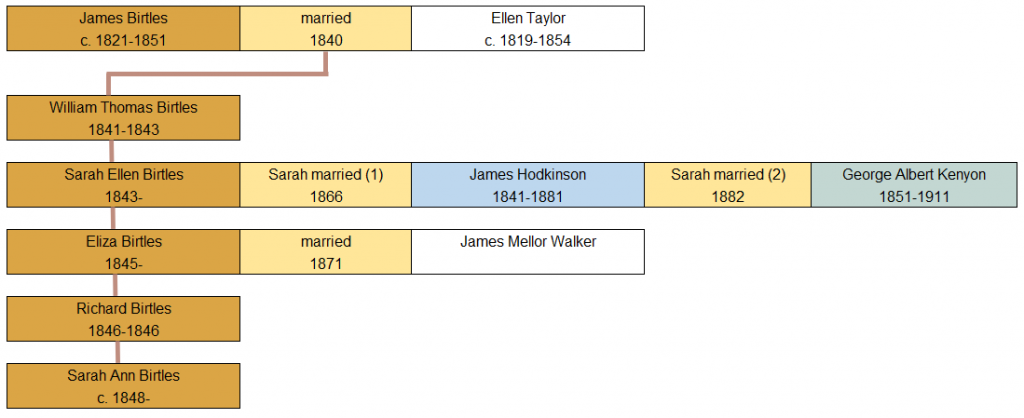

James Birtles married Ellen Taylor in 1840 and various records show that they had five children. I have copies of the birth certificates for the first four, but Sarah Ann Birtles turns out to be a problem child. I’ve been unable to find a matching birth certificate or any baptismal details about her, yet the 1851 census lists her as the three-year-old daughter of James and Ellen Birtles. The middle child, Eliza Birtles, spent at least six months in 1871 living in the Hodkinson home at 45 Welbeck Street, Ashton-under-Lyne.

Sarah Ellen Birtles' birthplace

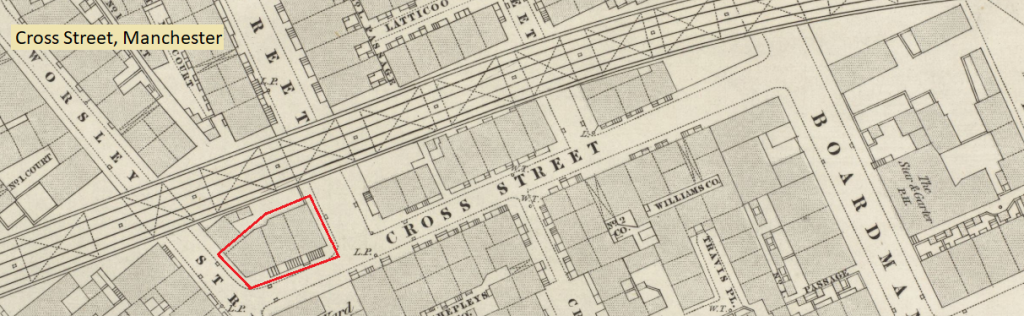

The southern side of Manchester Piccadilly station (known as Manchester London Road from 1847 to 1960) has platforms 13 and 14 on a viaduct. Many years ago, I often walked slowly up and down along the length of the platforms to pass the time whilst waiting for a train to take me to Stockport. What I didn’t know then was that the original viaduct was doubled in Victorian times and that when I reached the west end of the platforms, I was walking over part of the site of the demolished home – 3 Cross Street, which was one of the houses outlined in red on the map – where one of my ancestors, Sarah Ellen Hodkinson (Birtles), was born and lived for a number of years in the 1840s. Living there would not have been a pleasant experience with noise and air pollution from a major railway location just adding more misery to crowded, dirty and unhygienic slum housing.

The expansion of the railway station and associated trackwork meant that all the homes on the north side of Cross Street were demolished. However, part of the route of the actual street still exists but there continues to be nothing appealing about the immediate area.

Having worked my way through the 1851 census enumerator’s route for the above area, it was good to confirm what I thought, namely that the houses with odd numbers on Cross Street were on the north side and that they ascended from left to right. (It was not possible to work that out from the 1841 census, since no house numbers were recorded.) Sarah Ellen was born at 3 Cross Street. Assuming that the first of the highlighted houses was numbered as though it was on Cross Street (as the steps suggest), then Sarah Ellen was born in the middle house. If the first of the highlighted houses was numbered as though it was on Worsley Street, then Sarah Ellen was born in the right hand of the three houses. The map has a survey date of 1849.

The photograph shows the south side of the widened viaduct. In approximate terms, Cross Street ran on the left of the photograph, with the street being narrower than the tarmac route in the foreground. The fronts of the three houses highlighted on the map were in front of the grey railings. (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Back to the wedding certificate and the witnesses: William Henry Newton and Ann Clayton

William Henry Newton was having a busy few days: two days earlier, on Sunday 23rd December 1866 he married James’ sister, Lucy Hodkinson, at St Thomas’ Church in Heaton Norris, Stockport.

The other witness was twenty-year-old Ann Clayton who was a good friend of Sarah Ellen Birtles, James' bride. The 1861 census shows that Ann Clayton lived at 70 Hope Street in Ashton-under-Lyne; in that year Sarah Ellen Birtles lived at number 121 of the same street. In what were tightly knit communities, it is not too hard to imagine the two teenage girls getting to know each other, either at home or at work, and for a firm friendship to develop.

A church minister and a registrar

The couple were married by New Connexion Minister John Medicraft, who was 37 years old and who was born in Alnwick in Northumberland. However, the presence of a civil registrar was required by law when non-conformists married in their own churches, chapels and meeting-houses and this is why 35-year-old Irishman Samuel Fallone, the local Registrar of Marriages, was also at the ceremony.

This example of state-supported religious discrimination was completely at odds with the principles of the MNC and doubtless James Hodkinson felt annoyed at the presence of Samuel Fallone, not as an individual, but at what his attendance represented.

All done!

Once the ceremony was over, Mr and Mrs James Hodkinson, dressed in their Sunday clothes, left the chapel to begin married life together. It was still early in the day and a wedding breakfast beckoned. At least they had Christmas Day together. On Wednesday 26th December 1866 they were back at work – James stripping down and cleaning carding machines and Sarah Ellen Hodkinson weaving on a power loom. It would not be until 1875 that Boxing Day became an official bank holiday.

On 27th December 1868, two years and two days after their marriage at The Methodist New Connexion chapel, James and Sarah Ellen Hodkinson had their first child baptised. His name was Samuel and the christening ceremony took place according to the rites and ceremonies of the Church of England at St. Peter's Church, Ashton-under-Lyne. James and Sarah Ellen's commitment to the MNC was over.

James and Sarah Ellen Hodkinson's family

It is interesting to note that, out of his six children, only the first two – Samuel and John William – survived into adult life, a reflection of a deterioration of living standards following the Hodkinsons' move from their home in Church Street where the two boys had been born.

The death of James Hodkinson in 1881

On Friday, 4th February 1881, James Hodkinson died at his home at 25 Whittington Court, with his wife present. His death was certified by Dr J. Hamilton, L.R.C.P. (Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians) with the death certificate stating the cause to be 'bronchitis'.

James had spent about thirty years in working environments which were damp or humid or hot and where the air was thick with cotton dust or metal fragments or smoke or poisonous chemicals. It is no wonder, then, that James developed respiratory problems. It was also the 'wrong' season to be ill: in winter months, dense fogs often trapped smoke in industrialised areas of the country which led to an increase in the number of deaths from bronchitis.

This was the second James Hodkinson to die at 25 Whittington Court – just over a year earlier, two-year-old James Hodkinson had passed away at the same address.

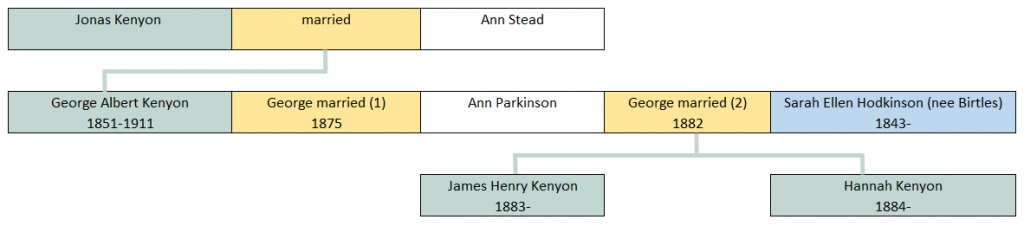

Sarah Ellen Hodkinson now had the stark reality of life with three children, aged eleven years, ten years and five months, to care for without the main breadwinner. The solution, as with so many who found themselves in the same predicament, was to re-marry. That being the case, in August 1882, Sarah Ellen Hodkinson started a new phase of her life when she married George Albert Kenyon. At that point she was about three months pregnant. The birth of James Henry Kenyon in early 1883 was followed in late 1884 by the birth of Hannah Kenyon, the last of her children.

This is part of the Kenyon family tree. The 1861 census lists seven children belonging to Jonas and Ann Kenyon with George Albert as the middle child.

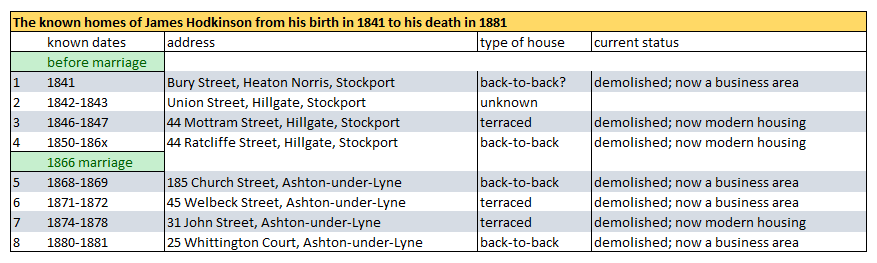

The homes of James Hodkinson from his birth to his death

A list of known homes and their known dates

The known dates of James' known homes are stated below. It was highly likely that he lived elsewhere, but such information is in the realms of unrecorded history.

Click here for information about James' first home in 1841.

Click here for James' homes from 1841 to 1866.

Click here for James' homes from 1866 to 1881.

Notes and sources for this page:

- Unless otherwise mentioned, this page is based on copies of birth, marriage and death certificates; census returns; and family documents and related items including photographs which are the property of Samuel Hodkinson.

- Correspondence. The Christian Magazine. (Manchester: Simms and Dinham, 1842.) No. 13. pp. 301-302.

- Sarah Mitchell, Daily Life in Victorian England. (Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996.) p.250.

- Pamela and Harold Silver, The Education of the Poor. (London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974.) p.103.

- Methodist New Connexion, The Jubilee of the Methodist New Connexion, a Memorial of the Origin, Government and History. (London: John Bakewell. 1848.) p.386.

- Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. (http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17306. 29 July 2012.)

- Edward Baines, History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain. (London: H. Fisher, R. Fisher and P. Jackson. 1840.) Scanned from illustration between p.182 and p.183.

- Morris and Co., Commercial Directory and Gazetteer of Ashton-under-Lyne and District. (Nottingham: Morris and Co. 1874.) pp. 59, 82 and 138.

- John Andrew, ed., History of Ashton-under-Lyne And The Surrounding District. (Ashton-under-Lyne: J. Andrew and Co. 1884.) p.286.

- Edwin Butterworth, An Historical Account of the Towns of Ashton-under-Lyne, Stalybridge and Dukinfield. (Ashton: T. A. Phillips. 1842.) p.68

This page was originally published on 12th August 2014 with a complete revamp by 30th July 2023.