George Hodkinson: 1841-1847 – the 1841 census to death

George Hodkinson: 1808-1841 – birth to the 1841 census

George Hodkinson: 1841-1847 – the 1841 census to death ... this page

Stockport railway viaduct was built during the time that the Hodkinsons lived in Heaton Norris. They certainly will have witnessed its construction but, being hard at work in cotton factories, would have missed the first locomotive to run over its lines on 16th July 1841. This illustration is from 1853.

George Hodkinson

- Born: Saturday, 10th December 1808

- Married: Sunday, 23rd September 1832 (age 23)

- Four children: two boys and two girls

- Died: Monday, 10th May 1847 (age 38)

Bearing in mind the shared history of members of the Hodkinson family, some of the information on this page has been repeated on other pages about other Hodkinsons.

George Hodkinson and family in 1841

The Hodkinson family in 1841

In June 1841, the Hodkinson family was comprised of married couple George and Hannah, and three children – Mary, Lucy and James. Their first son, William, had died two years previously. The family had a long-term lodger who was living in the same house. He was unrelated, but shared the same surname. His name was William Hodkinson, and he was trouble!

Census night, Sunday, 6th June 1841

All households received census forms shortly before census night which was Sunday, 6th June 1841, with the completed forms due to be collected the following day. For the purpose of the 1841 census, the township of Heaton Norris was split into 21 enumeration districts, with the Hodkinson household being in district 12 which was, in general terms, the Hope Hill area.

Nationally, there were thousands of households without anyone who was literate enough to complete the forms beforehand and the Hodkinsons were no exception. In some cases, literate friends or relatives would have helped, but what was more likely was that the enumerators themselves would have helped to complete the forms when calling at homes on Monday, 7th June 1841.

The Hodkinson household on Sunday, 6th June 1841

On the night of Sunday, 6th June 1841, there were six people living in the Hodkinson household: three adults and three children.

George Hodkinson was the head of the household. He and his wife, Hannah Hodkinson (formerly Oldham), have their employment listed as being in the cotton industry. If they were actually in work, they were lucky. Unemployment was high: Stockport, after all, was in a deep depression, centred on the cotton industry, which had begun in 1837 and which showed no signs of recovery until 1843. The third adult was lodger William Hodkinson (unrelated) who had spent most of his life in the army and who had found lodgings with George and Hannah. Living with the three adults were Hannah and George’s three children: seven-year-old Mary Hodkinson, five-year-old Lucy Hodkinson and baby James Hodkinson, who was just over two months old. There would have been another child, but seven-month-old William Hodkinson had died in 1839 from smallpox.

There wasn’t much more information that the enumerator needed – once he (all 35,000 or so enumerators were male1) had names, ages, sex, occupations and whether or not the occupants were born in the county where the census was being held, then he could be on his way. The entries wouldn’t have taken long to complete but doubtless there was some general chatter about other matters. Perhaps, even then, the great British pastime of discussing the weather cropped up: after all, the previous winter had been severe, followed by high rainfall in May which was continuing into June; perhaps there was talk about what was in the census and about the census itself since, it has to be remembered, this was the first time ever that a census on this scale had been carried out; or perhaps there were some comments about the new baby. Nevertheless, a few minutes chatter at each household could ultimately add hours to the enumerator’s work so it not likely that he stayed longer than necessary.

The neighbours in 1841

The Hodkinsons in 1841 were living on Bury Street in Heaton Norris and probably lived in one of the houses about half-way up the street as marked in red on the map in the first part of the story of George Hodkinson. The homes here were back-to-back which meant that the Hodkinsons lived in very cramped conditions. Elsewhere on the street were houses that were two-up, two-down – and therefore much roomier than the Hodkinsons' home – but the 1841 census shows some of these had occupancy levels of ten or eleven people. As it was, the occupancy level for all homes in Stockport was an average of 5.1, a figure which remained more or less the same from 1831 to the end of the century.2

The 1841 census shows that two families shared the house immediately to the south of the Hodkinsons. One of the families consisted of Charles Sheed and his two sons, Thomas and Henry; the other family was John Thompson, his wife Sarah, and their five-year-old son and nine-month-old daughter. The Hodkinsons’ other neighbours were Edward Bowes and his wife Mary; they must have felt fortunate that just two of them shared one house, even though it was a back-to-back. In this set of three houses, the vast majority of those who were of working age were employed in the cotton industry.

Ten years on, most people – including the Hodkinsons – had moved from the two Bury Streets but some remained: Thomas Glover, Mary Hibbert, Peter Harrison, Betty Bredbury, Elizabeth Dickens and Samuel Gosling are the head of household names which feature in both the 1841 and 1851 censuses.

As a final comment on housing for workers in Stockport, it is worth repeating this oft-quoted extract from The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844 by Frederick Engels:

Stockport is renowned throughout the entire district as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes, and looks, indeed, especially when viewed from the viaduct, excessively repellent. But far more repulsive are the cottages and cellar dwellings of the working-class, which stretch in long rows through all parts of the town from the valley bottom to the crest of the hill. I do not remember to have seen so many cellars used as dwellings in any other town of this district.3

An ex-army private destroys George Hodkinson's marriage

The marriage between George and Hannah had started off well. By 1841, by which time they were living in Heaton Norris in Stockport, Hannah had given birth to four children: Mary, Lucy, William and James, although William tragically died at seven months.

What they both didn’t know was that their marriage was to suffer a fatal blow when they answered a knock at the door during 1839. Standing there at 5ft 6in with light brown hair and grey eyes was another Hodkinson. It was 41-year-old William Hodkinson, needing somewhere to live after being discharged from the 39th Regiment of Foot following nearly 26 years of military service.

From a financial point of view, having William as a lodger was good news for George – William's financial contribution to the household budget was most welcome. From the point of view of relationships in the home, it was bad news for George: Hannah and William fell in love with each other. Whether George realised that Hannah and William were in a relationship or whether Hannah and William told George about what was going on will never be known, but at some point between 1841 and 1842, George left Hannah, his children and the family home.

By January 1842, the rest of the Hodkinsons, including marriage-destroyer William, were living in Union Street in the increasingly densely populated Hillgate area of Stockport, about one mile south-east of their former address.

At least one family tree on a genealogy site states that William and George were brothers, but I have found no firm evidence that they were related. The census of 1841 has an enumerator's marking which indicates that, within the one house, George's household of five was separate to William's household of one (himself) which suggests no familial ties, otherwise the enumerator would have recorded one household for everybody. William was born in Heaton Norris and joined the army when he was fifteen and still a resident of Heaton Norris. It seems logical that he headed back there after leaving the army, knowing no other place to go. When William left the army, did he look for lodgings in Heaton Norris and found a family willing to have him, with the same surname being a co-incidence? Or was there more to it than that?

Were George and William Hodkinson still drinking together in 1841?

Public houses in industrial towns in the early nineteenth century – and beyond – featured highly in the social life of workers and Stockport was no exception, being able to boast 103 ‘locals’ in 1833.4 (This compares quite favourably to the total of four that George knew in Cheadle! )

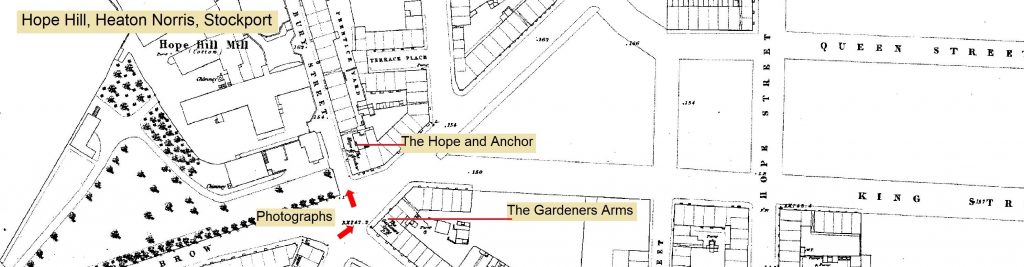

The adult males in the Hodkinson family – George and William – had a choice of two that were reasonably nearby. At the corner of Bury Street and George Street stood the Hope and Anchor, with the Gardeners Arms just across the road.

The two public houses shown on this 1851 Ordnance Survey map (reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland) were the nearest for George Hodkinson and William Hodkinson, with their location at the bottom of Bury Street. The buildings of Hope Hill Mill can be seen opposite the Hope and Anchor. Doubtless George and William frequented these hostelries, until they fell out when George realised that his wife, Hannah, and William were having an affair.

In 1841, the landlord of the Hope and Anchor was James Haughton who lived there with his wife Nancy and their two children: Elizabeth, who was in her early twenties, and three-year-old James. This was the nearest public house to the Hodkinson household and it is more than likely that George Hodkinson and William Hodkinson frequented the place, while Hannah Hodkinson would have stayed at home, looking after Mary, Lucy and baby James. Sometimes George may have gone drinking without William who would have stayed at home, enjoying his affair with Hannah.

This photograph was taken from the bottom of Lower Bury Street, as indicated with the red arrow pointing roughly north on the map above . The Hope and Anchor public house in Heaton Norris, Stockport, was situated on the right of the photograph. The pub was demolished to make way for the 1860s railway expansion by the Cheshire Lines Committee. The railway, its associated sidings and the bridge which spanned the bottom of Bury Street no longer exist, apart from two columns (see below). (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

The bottom red arrow on the map above indicates the direction from which this and the next photograph were taken. The photograph above, of the Gardeners Arms in Heaton Norris, Stockport, is from the 1960s and shows how close the building was to the railway tracks of the Cheshire Lines Committee. The map pre-dates the building of railway. George and William Hodkinson would have enjoyed a few pints here – until they fell out.

As in so many industrial towns, anyone who tired of one public house generally did not have far to go to find another. If George Hodkinson and William Hodkinson wanted a change from the Hope and Anchor, then they could simply cross the cobbles of George Street and go into the Gardeners Arms which was more or less opposite.

George Hodkinson's lonely death on Monday, 10th May 1847

With George Hodkinson out of the way, his estranged wife Hannah Hodkinson and her paramour William Hodkinson moved to Union Street, Hillgate, Stockport. In an era when two unmarried adults living together could be met with widespread disapproval, it was fortunate that they had the same surname. They were still Mr and Mrs Hodkinson – although not the same couple as stated in the church marriage records, but their new neighbours were none the wiser. In August 1843, Samuel Hodkinson was born, the first of Hannah and William’s five children.

In the next few years, whilst the Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson family was growing, George was doubtless continuing to work as a cotton spinner, if he could find work, and at least some of his time was spent in what is now known as the Northern Quarter of Manchester. In 1847 the area’s population – in common with other places – was continuing to grow dramatically, with a huge influx of Irish immigrants fleeing famine in their own country and whose fate was to live with others in dire poverty and filth, and experience nothing but an abject quality of life.

A striking testament to the problems faced in Manchester is that, by 1847, the workhouse on Bridge Street could no longer cope with the demands placed on it and so additional accommodation for 600-800 inmates was created by leasing premises which once were Barratt’s Mill, at the northern end of Tib Street. It opened in January 1847 and George Hodkinson was one of the first inmates, fitting the main criterion for admission which was being able-bodied enough to earn relief in return for labour.

This Ordnance Survey map (reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland) was surveyed in 1848, a year after George Hodkinson died in the workhouse on Tib Street, Manchester, which is circled in red. The workhouse was also called the House of Industry; doubtless George and his friends would have made some solid down-to-earth comments about that. The photograph of the site of the workhouse shows it is now occupied by a red-bricked residential building and the smaller of two grey commercial units. (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

In 1847, Manchester experienced an outbreak of typhus fever, a disease associated with poor sanitation and crowded living conditions and is transmitted by body lice. The symptoms of the disease include a severe headache; a high fever; a rash that begins on the back or chest and spreads; confusion; low blood pressure; and severe muscle pain. Even worse are the complications which can set in, such as internal bleeding and hepatitis, and which can be fatal. Depending on the stage of the fever, not everyone who contracted it died. George Hodkinson, however, was one of the unfortunate ones, for when he became ill with typhus fever, complications did set in and the workhouse which was sustaining him with food and accommodation in return for his labour, was also the place where he died on Monday, 10th May 1847. He was 38 years old.

Manchester Cathedral records show that George was buried three days later, but his actual place of interment is not known. It wasn’t in the Cathedral’s small graveyard, or in one of its three ‘overspill’ graveyards, since all their closures predate George’s death. A bit more research needed here, then!

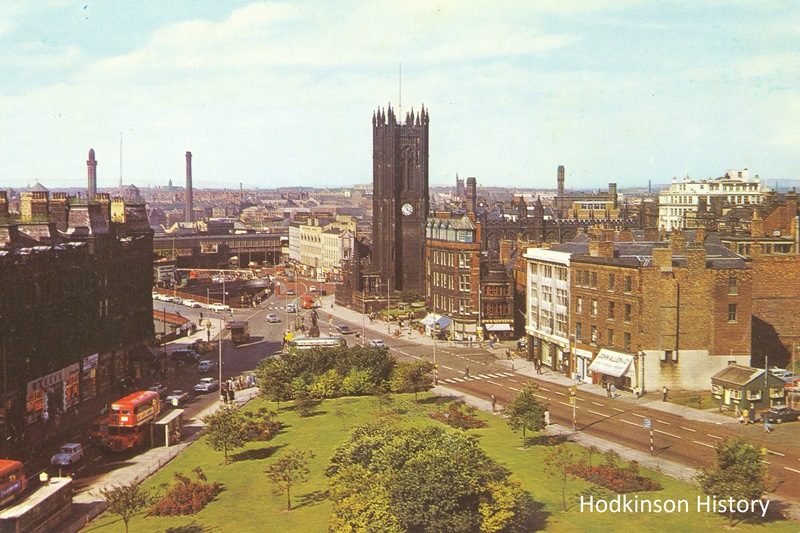

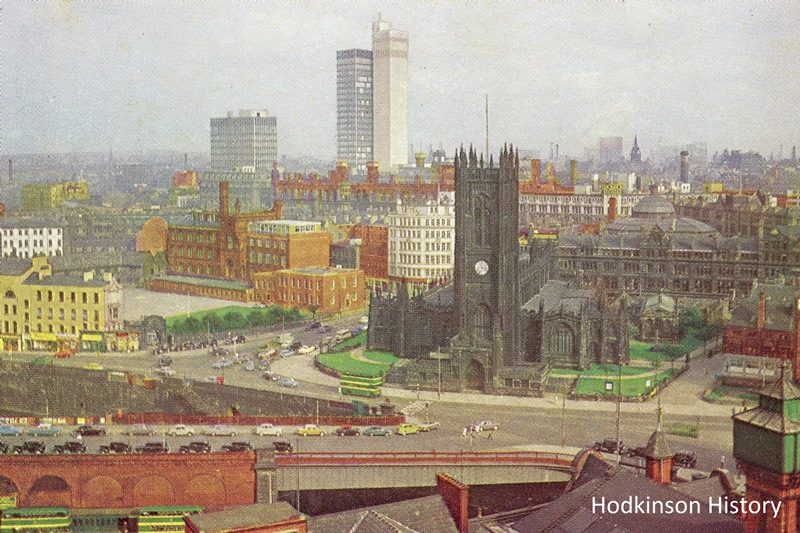

Manchester Cathedral was a short distance west of the workhouse on Tib Street where George Hodkinson died. Cathedral records give the date of his burial, but the graveyard where he was interred is not known. These views of the Cathedral are from family postcards purchased in the early 1970s. (Postcards: property of Samuel Hodkinson.)

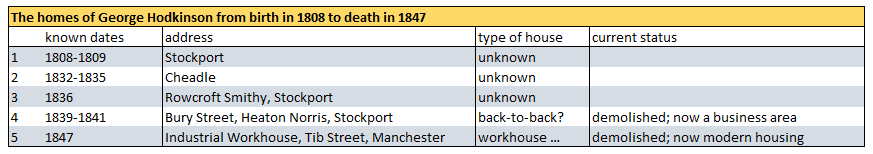

George Hodkinson's known homes

A list of known homes and their known dates

The known dates of George's known homes are stated below and more details about them are elsewhere on this page, and on the first page about George's life. George would have lived at some of these addresses for much longer than the date(s) given. Additionally, there is no doubt he lived at other addresses – I just wish I knew where!

George Hodkinson's family after his death

Somehow the news of the death of George Hodkinson became known to Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson. These two, who since around 1841 had told everyone that they were married, now could plan their actual wedding. The problem was that the duplicitous duo could not marry in their local parish church of St Thomas, Hillgate, for that would expose the truth that they were living together and, a matter of great shame, that they had three illegitimate children. The solution was to marry in another parish and so they decided to head west to St James’ Church in Didsbury. Not only was the church in a completely different ecclesiastical parish, but it was also over the county border in Lancashire.

The couple married on Sunday, 8th October 1848. Prior to the ceremony and within the confines of the church, it was the first time in years that they could be open that they were not married. However, they could not be open that they had been living together and, for the purposes of the wedding certificate, William Hodkinson said he lived in Heaton Mersey and Hannah Hodkinson said she lived in Heaton Norris, rather than declaring Hillgate as their shared address. A few lies to the vicar wrapped everything up nicely and they returned home the same day, back to their children in cramped accommodation on Ratcliffe Street. Hannah's second marriage was a secret marriage to be shared with nobody but it freed the couple from a six-year lie.

A huge number of questions can be asked about the life and death of George. Was contact maintained between George and his children and his estranged wife during the years following the breakdown of the marriage? How did Hannah and William hear of his death? Did they feel any remorse? Was this the moment they had been waiting for? And so on...

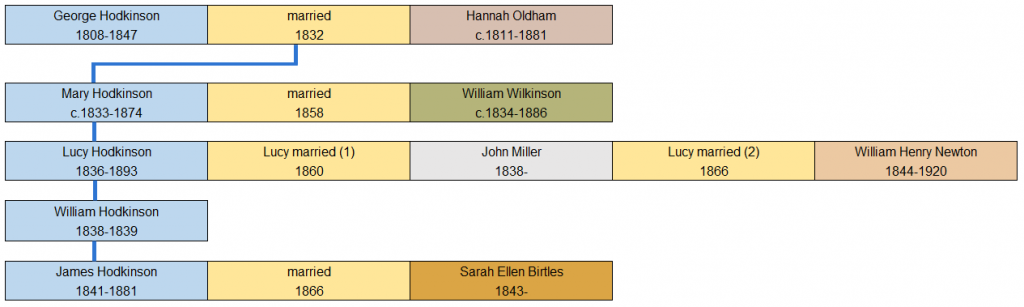

The four children of George Hodkinson and Hannah Hodkinson

Mary Hodkinson was probably born in the first few or middle months of 1833. She married William Wilkinson in 1858 and died in 1874 in Stockport.

Three pages cover the life of Mary.

More information about Mary’s birth in 1833, and the years up to 1841, can be found here.

Mary’s life from 1841 to 1855 (when her first child was born) is here.

Mary’s life from 1855 to her death in 1874 is here.

Lucy Hodkinson was born in the first few months of 1836. She married twice. Her second marriage was to William Henry Newton. They emigrated to Australia where she died in 1893.

Three pages cover the life of Lucy.

More information about Lucy’s birth in 1836, and the years up to 1841, can be found here.

Lucy’s life from 1841 to 1860 is here.

Lucy’s life from 1860 (when she first married) to her death in 1893 is here.

William Hodkinson's death predated that of his father, with William's death taking place in 1839. There is more information about him here.

James Hodkinson was born in 1841 and carried on the Hodkinson surname of this branch of the family.

Three pages cover the life of James.

More information about James’ birth in 1841 can be found here.

James’ life from 1841 to 1866 is here.

James’ life from 1866 (when he married) to his death in 1881 is here.

George's wife, Hannah Hodkinson, had five more children (Samuel, Elizabeth, Ellen, William and John) with William Hodkinson as the father. Three of the children were born before Hannah and William married in 1848.

George Hodkinson: 1808-1841 – birth to the 1841 census

George Hodkinson: 1841-1847 – the 1841 census to death ... this page

Notes and sources for this page:

- Paul Carter, Kate Thompson, Sources for local historians. (Chichester: Phillimore, 2005.) p.35.

- Peter Arrowsmith, Stockport, A History. (Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Council. 1997.) p.175.

- Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. (http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17306. Accessed 29 July 2012.)

- Peter Arrowsmith, Stockport, A History. (Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Council. 1997.) p.213.

This page was originally published on 23rd February 2020 with the latest updates made on 20th February 2025.