John William Hodkinson: 1896-1942 – marriage to death

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1896 – birth to marriage

John William Hodkinson: 1896-1942 – marriage to death ... this page

John William Hodkinson: 1900-1917 – three times a soldier

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1942 – eighteen homes

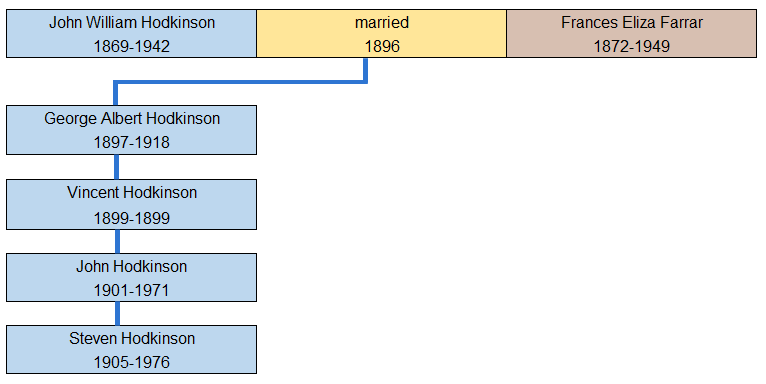

- Parents: James Hodkinson and Sarah Ellen Hodkinson (remarried as Kenyon)

- Born: Monday, 20th September 1869

- Married: Saturday, 4th April 1896 (age 26 years and 6 months)

- Four children: all boys

- Died: Monday, 2nd February 1942 (age 72 years and 4 months)

What a difference a generation can make

Life as a child and as a young adult had been tough for John William Hodkinson. He had experienced grinding poverty in a variety of homes in Ashton-under-Lyne. He had to come to terms with the deaths of five brothers and sisters and of his father by the time he was 20 years old. He had to adjust to new family relationships when his mother remarried and had children with her second husband.

The effect of all of this on John William could have been profoundly negative, but it wasn’t. He grew up to be a determined and resourceful individual who did not give up easily in the face of challenges. From the age of eleven, his stepfather (George Albert Kenyon) was a positive influence and encouraged him to become a moulder and core maker, skilled work which earned him a good salary and status. John William’s regard for his stepfather was reflected in naming his first son after him, but none of his children (all boys) were given the name of his natural father (James), either as a first or second name.

John William Hodkinson’s social standing was also indicated by his right to vote. Prior to 1918, it was necessary to own a property or pay rent above a designated amount in order to be allowed to vote. In the case of John William, it was the latter criterion which came into play and which accounts for his name on local electoral registers more or less from the time that he was married.

Marriage was the start of a new era for John William. Yet, although happily married with Frances Eliza, he could not shake off tragedies. Vincent Hodkinson, their second child died in 1899, not having reached the age of three months. Their first son died in 1918, a soldier of the Great War. John William Hodkinson may well have been resilient, but he struggled with ill-health. Deafness, vertigo and rheumatism – probably due to his working environment – started to have a major impact well before he was forty. An army medical report of 1917 states that John William had been laid up for six months before enlistment due to (in John William’s own words) “paralysis of the brain”. His health continued to deteriorate particularly badly in the 1930s, necessitating stays in hospital.

John William Hodkinson's working life – mainly as a moulder/core maker

Although he worked as a weaver at a young age, John William completed an apprenticeship as a core maker, an occupation that he stayed with for the rest of his working life. In those cases where he had to declare his occupation on official forms, he classified himself as a "core maker", apart from one case where he said he was a "moulder". When he died, his wife stated that he was a core maker and moulder.

John William's job - a praiseworthy occupation

The occupations of iron moulder and core maker had high status, often reflected in contemporary literature.

In 1887, an article about a locomotive foundry commented that

… mouldings of all sizes and shapes are being made … over which the moulder expends as much care and pains as if he were a sculpture at work upon some tender piece of statuary.4

In 1902, the author of a book on modern iron foundry practice wrote

Of the many branches of the engineering trade, there are few which offer such scope for the exercise of mental power and perceptive faculty as the construction of a mould … and a careful study of the moulder’s art by the pattern maker and draughtsman is essential if thoroughly satisfactory work … is to be produced.5

In 1921, a book entitled Iron Founding spoke of

… the success or otherwise in dealing with (castings) … depends entirely on the individuality of the moulder, and readiness in dealing with problems … is one of the attributes of a skilful moulder.6

In 1922 an article specifically about core makers which was published in The Foundry Trade Journal commented that the degree of skill necessary in the making of cores was not less than that required in the preparation of moulds and went on to point out the that the making and assembly of cores for highly complicated work was more difficult than the preparation of moulds.7 The chances are that John William never read any of the compliments above, but he knew his job had a good status and, importantly, because of that, he earned a good wage. In turn, his pay meant that he could rent modern two-up, two-down houses for his family who were well provided for.

Two known employers of John William Hodkinson

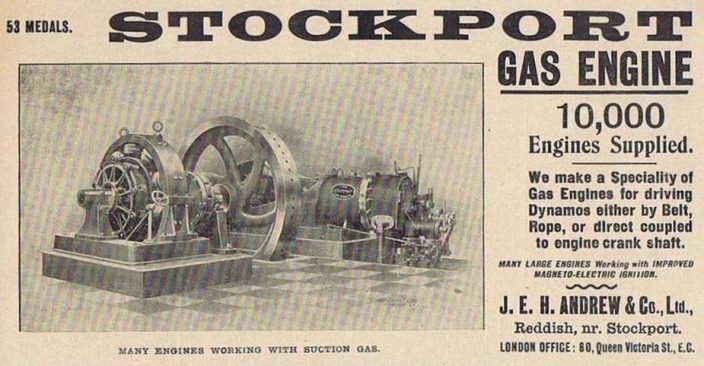

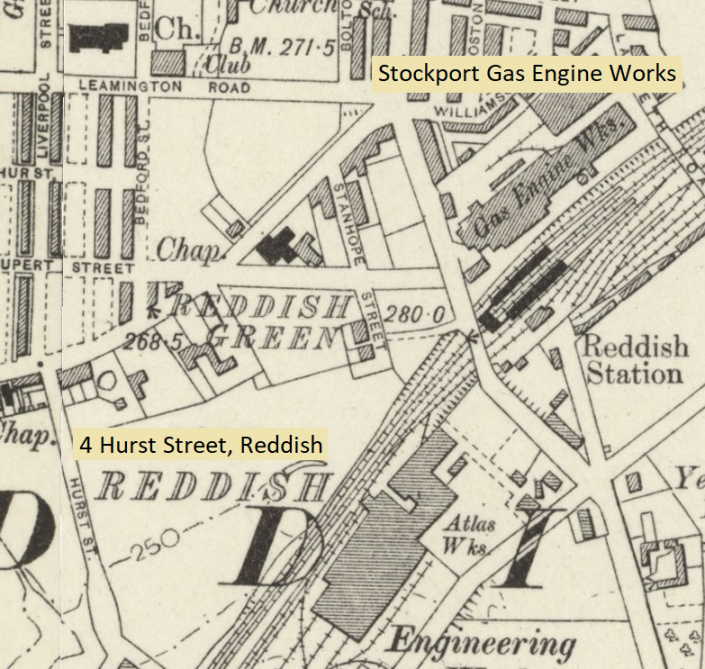

1. The Gas Engine Factory, Reddish

A core maker's dream? This 1904 Stockport Gas Engine advert for J.E.H. Andrews in Reddish shows the kind of engine that John William would have helped to make.

Unfortunately, very little is known of John William's workplaces, but the censuses of 1911 and 1921 provide some information.

The 1901 census states John William was a core maker in an engineering works. The 1911 census states that he was working at a "Gas Engine Factory" as a core maker. This factory was in Reddish, namely, J. E. H. Andrew and Company of Reddish, which was established in 1878 and absorbed by R Hornsby and Sons of Grantham in 1906 and the only one in the area to make gas engines.

Assuming – and this could be a big assumption – that the engineering works of the 1901 census was the same factory as the 1911 census, then John William Hodkinson spent at least a decade at the gas engine works.

An article in the Iron and Steel Journal of 1899 commented that the works

... are of considerable size, are situate adjoining the London and North-Western Railway Station, Reddish, ten minutes’ walk from Reddish Great Central Railway Station, and a quarter of an hour’s walk from Heaton Chapel Station, London and North-Western Railway. The works are devoted solely to the manufacture of Stockport gas-engines, in sizes from 1 horse-power to 250 horse-power. The factory is driven by gas-engines worked from fuel-gas made on the premises … The works contain many examples of the most modern tools and labour-saving appliances, including electric travelling cranes. They are lighted throughout by the electric light, and are capable of turning out about 16 gas-engines per week.8

From about 1903 to 1906, John William lived at 4 Hurst Street in Reddish – a very convenient short walk away from the factory site next to the railway station. When the family moved to Stockport, he most likely travelled by rail to work, with the train part of the journey taking six to seven minutes.

Despite the positive aspects of working at the gas engine works, it was during the years at the factory that John William began to suffer badly from rheumatic pain. However, that did not stop him from making a long sea voyage to Australia. (See below.)

John William and his family lived on Hurst Street from at least July 1903 to at least June 1906. This home was conveniently situated for a short walk to work at the gas engine factory.

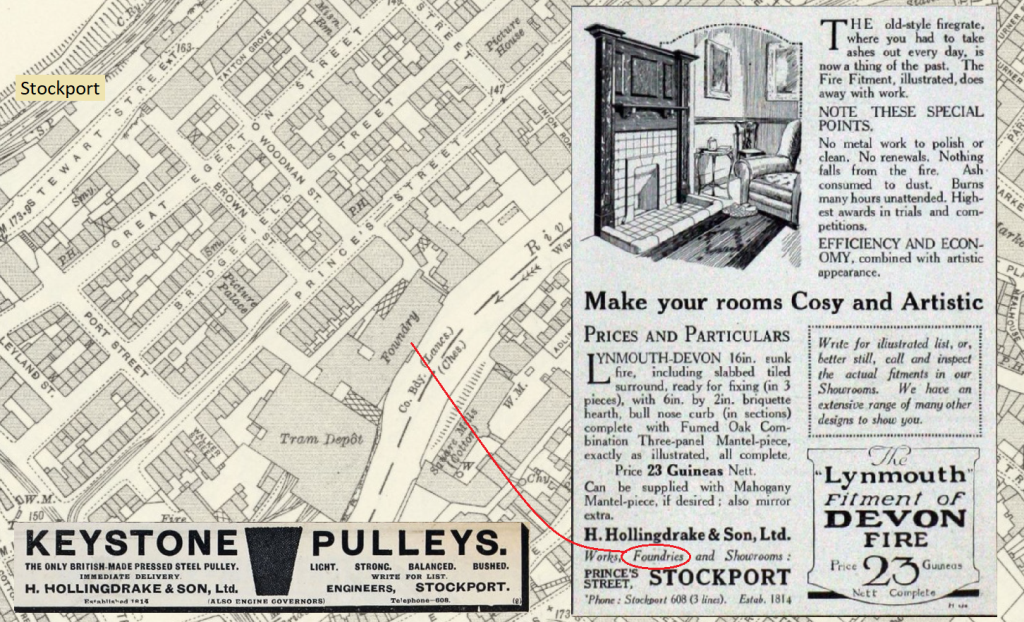

2. Henry Hollingdrake and Son, Iron Founders, Stockport

John William’s trip to Australia in 1911 (see the next section below) was followed by service in the British Army during 1914-1915 and 1917, with discharges on medical grounds. Where he worked before, between, and immediately after those events is no longer known. However, the census of 1921 reveals that John William Hodkinson was working at Henry Hollingdrake and Son, Iron Founders, 65 Prince’s Street, Stockport, as a core maker. (Did he get employment here in 1917 after leaving the army?) He was then almost 52 years old. There is no recorded information about where he was employed from 1921 to retirement age. His army records show that he suffered from rheumatism, deafness and vertigo, all of which worsened in subsequent years, having a major adverse impact on his ability to work.

The listing above is from Kelly’s 1914 directory for Cheshire. H.Hollingdrake and Son Limited was founded a hundred years earlier and was still thriving, having successfully adapted its business practices to take advantage of the massive changes in commerce and industry over a century. As seen from the listing and the adverts from 1919 and 1921 (Acknowledgements to Grace's Guide9), the company’s portfolio was diverse. The map, which has a revised date of 1917, shows the location of the foundry where John William worked.

John William Hodkinson's journey to Australia

Over a hundred years later, it is a mystery why

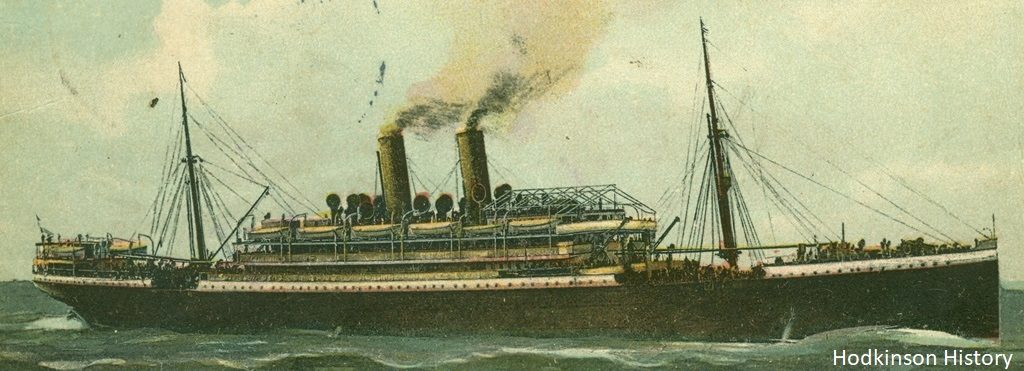

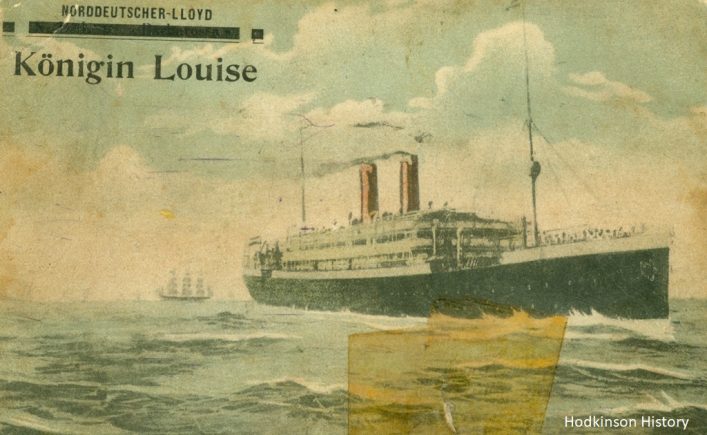

John William Hodkinson's 1911 journey to Australia was on the SS Konigin Luise which began its journey in Bremen, and then called at Antwerp (where John William boarded), Southampton, Algiers, Genoa, Port Said, Aden, Colombo, Fremantle, Adelaide, and for John William, the next stop at Melbourne marked the end of a very long journey. The SS Konigin Luise, however, had not quite reached its final destination as it had to carry on to Sydney. Click on the icons to see the ports of call.

In October 1911, 42-year-old John William Hodkinson said goodbye to Frances Eliza, his 39-year-old wife, and to his three children: George Albert, who was thirteen, John who was ten, and Steven who was six, and started his journey to Melbourne. The reason why he should make this journey has been lost during the course of many decades, but there are a few suppositions to fill the knowledge gap – but more about these further down this page.

The first leg of the journey to Melbourne: Stockport to Antwerp

Armed with a third-class (steerage) ticket for the SS Konigin Luise, the ship which would take him to Australia, John William headed for Antwerp, his boarding port. How he got there is not known, but probably the most straightforward route would have been by train from Stockport to a port on the east coast such as Goole, Hull or Grimsby before making the sea journey to Antwerp. John William had some time to look around the city – certainly a day or two at least – and commented that it was a fine place for buildings.

The German shipping company Norddeutscher Lloyd, the owner of the SS Konigin Luise, on which John William was a passenger, made this announcement in 1906 regarding a 43-day journey time from Southampton to Sydney.

On Saturday, 28th October, 270 passengers boarded the ship and all, apart from one, were steerage. Of the 270, about 240 were listed as being "English"; 21 or so were listed as "Welsh", "Irish" and "Scotch"; with the rest being other nationalities. The next morning, at 5 o'clock, the ship set sail on the 15,000-mile journey which would last over 40 days.

The second leg of the journey to Melbourne: Antwerp to Melbourne

The SS Konigin Luise had started its journey in Bremen before calling at Antwerp – where John William boarded – and then called at Southampton. John William would have watched as almost one hundred passengers boarded at Southampton and would have thought how simpler it would have been if he had travelled from Stockport to Southampton by train and boarded the ship there. Yet the shipping company would not allow that – John William had bought the cheapest possible ticket which gave him steerage accommodation and steerage passengers from the British Isles had to board in Antwerp. Those from the British Isles with first- or second-class tickets could board at Southampton if they wished.

In October, John William wrote the postcard above to his wife and, at that stage, was impressed with the smoothness of the journey commenting "You can't tell that you're sailing." He also said that it was very cold as they passed through the Straits of Dover and that his overcoat came in handy. The sellotape repair to the rip in the postcard was carried out about forty years later by John William's youngest son and so has become part of its history. (Postcard: property of Samuel Hodkinson.)

The reason why British Isles steerage-passengers boarded at Antwerp may have been because Southampton sailing schedules, bearing in mind the time between low and high tides, did not allow for all passengers to board the ship in one go. Somehow the numbers embarking had to be reduced and the solution was for those with the cheapest tickets to board elsewhere, namely, Antwerp.10

Only one person joined at Antwerp who was not a steerage passenger. She was a first-class ticket holder, Miss G Robin, who was 35, English, with her occupation given as "Barrister". Separate arrangements would have been made for her to join the boat – after all, there is no way that she could have joined a steerage-class queue.

On the way to Melbourne, John William witnessed more passengers joining the ship until there were 671 on board, of whom 401 were in steerage including 24 children.

Those that John William came into contact within steerage accommodation came from a wide variety of work backgrounds. The occupations listed included: butcher, carpenter, engineer, musician, labourer, trader, soldier, miner, farmer, farrier, printer, waiter and gardener. The nationalities were also diverse. Apart from those from the British Isles, other nationalities included: Danish, Russian, German, Sinhalese, Spanish, Italian and Swiss.

Certainly, John William would have formed friendships with many of those in steerage and would never have been short of somebody to chat with, including, maybe, the oldest person making the trip, a Mrs F Hill, who was 82.

In the first week of December 1911, with goodbyes said to other passengers, John William Hodkinson disembarked from the SS Konigin Luise and set foot on Australian soil, the third Hodkinson to do so. His step grandfather, William Hodkinson (1798-1858), was stationed in New South Wales from about 1827 to 1833 as a private in the 39th Regiment of Foot. His aunt, Lucy Hodkinson (1836-1893), landed in Queensland in 1870 when her family emigrated there. A more recent member of the Hodkinson family spent time in Australia, but eventually returned to the UK.

So ... why did John William travel to Australia?

So much for John William's actual journey to Melbourne. But why go there?

In trying to work out the answer, the main issue is how his family were provided for when he made his trip. He would have had to give up his job at the gas engine factory. In terms of travelling time alone, he was away from home for about three months. During this time his family needed to live – perhaps they had savings to sustain them for at least that length of time, but how likely was that? Within that context, it is hard to believe that John William went to Melbourne just for a visit or some kind of holiday and left behind his family.

It could be that John William went to visit relatives. After all, his aunt, Lucy Hodkinson (who married William Henry Newton in 1866), had moved there about four decades earlier. However, Lucy's descendants lived in a town in Queensland, about a thousand miles away from where John William landed.

What does make some sense is that John William went to Australia for long-term temporary work. When in Melbourne, he wrote to his wife letting her know where to send mail to him – in his name, care of the post office in Melbourne, and marked, "to be called for", which was hardly the indication of an intention of a short-term visit.

How long John William remained in Melbourne is not known, but eventually, when more ocean liner passenger lists have been digitalised and made public then, hopefully, his return journey details will be available. The length of stay may then help to make sense of why he made the journey.

Of course, there are all those other unanswered questions about his time in Australia, including how he found accommodation and where it was. What is certain, however, is that John William was back in Stockport at the start of World War 1. It wouldn't be long before he would be Private John William Hodkinson, a member of the 3rd Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment.

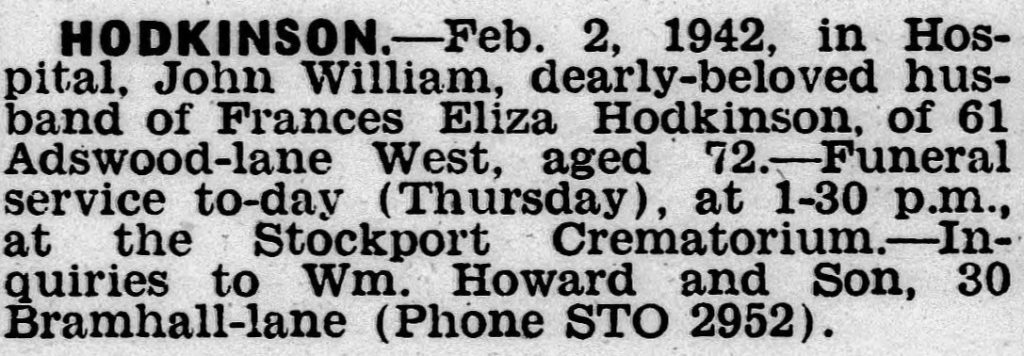

The death of John William Hodkinson on Monday, 2nd February 1942

As John William's health deteriorated after the war, he became a frequent visitor to the infirmary at the workhouse in Stockport. Some of the stays were long, with, for example, a family diary detailing such a visit in 1926. The 1939 Register also shows that he was in the workhouse at the time that the Register was taken. John William struggled on with ill health until Monday, 2nd February 1942 when he died. His wife, Frances Eliza, was with him in his final moments. Three days later, on Thursday 5th February, his funeral service was held at Stockport Crematorium, with this information being published on the same day in the Stockport County Borough Express, as above.

On John William's death certificate, Dr William More provided three related causes for his death.

The first was bronchopneumonia, which is a bacterial lung infection. The risk factors for developing such a condition relevant to John William appear to have been his age, his history of smoking and, bearing in mind that his death occurred in winter, perhaps recent respiratory infections, such as influenza also had a part to play.

The chest infections contributed to the cause of the second stated reason for death, namely, myocarditis, the inflammation of the heart muscle.

Sadly, John William’s heart had been in a bad way for some time. His age, smoking and probably a high-fat diet were the factors in his life that brought about arteriosclerosis – the clogging of arteries with fatty substances – which was the third reason given for his death. Compared to current medical research and practice, the knowledge and understanding of the harmful effects of a poor diet and of the dangers of smoking were at a basic level when John William died. Unwittingly, he may well have made things even worse for himself. A story passed down the generations relates to John William’s love of pipe smoking. When he put sugar in his tea, he often stirred it, not with a teaspoon, but with the stem of his pipe. This meant that any poisons from the tobacco still in the stem were mixed into his tea, creating a toxic brew.

John William Hodkinson's family after his death

John William was survived by his wife and two of his four children.

His wife, Frances Eliza Hodkinson, was 69 years old when John William died.

Frances Eliza Farrar was born in a house in the High Street, Kidsgrove, Staffordshire, on 12th February 1872. By 1881, her family were living in Dukinfield with the census of that year stating that she was a scholar. Ten years later, the 1891 census gives her occupation as a cardroom hand; her 1896 marriage certificate and the censuses of 1901 and 1911 provide no information about her occupation; she is performing “Home Duties” in the 1921 census; and, according to the 1939 Register, she is carrying out “unpaid Domestic Duties” in that year. Frances died on 3rd August 1949 at 61 Adswood Lane, Stockport, the house that she and her family moved into in 1911.

As the years go by ... the images of Frances Eliza Hodkinson (Farrar) are cropped from undated photographs from about the 1890s to the 1940s. (Photographs: property of Samuel Hodkinson.)

John William's first son, George Albert, died in 1918 of war wounds. His second son, Vincent, died in 1899 from bronchopneumonia.

John William's third son, John Hodkinson, was 41 years old and living in Portwood with his wife when his dad died. World War II was into its third year but John, as an x-ray machine operator, was exempt from military service. However, he supported the war effort as a volunteer part-time ARP (Air Raid Precautions) warden. John Hodkinson died in 1971 and his wife died in 1993. They had no children.

Steven Hodkinson was 36, unmarried and living at home, when his father died. A 1943 document shows he was involved in wing construction for military aircraft at the Fairey Aviation company in Errwood Park, Stockport. That gave Steven exemption from national service. He married after the war.

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1896 – birth to marriage

John William Hodkinson: 1896-1942 – marriage to death ... this page

John William Hodkinson: 1900-1917 – three times a soldier

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1942 – eighteen homes

Notes and sources for this page:

- Unless otherwise mentioned, this page is based on copies of birth, marriage and death certificates; census returns; and family documents and related items including photographs which are the property of Samuel Hodkinson.

- www.tameside.gov.uk., Tameside Image Archive. (http://www.tameside.gov.uk/history/archive.php3. 15 June 2010.)

- www.tameside.gov.uk., Tameside Image Archive. (http://www.tameside.gov.uk/history/archive.php3. 15 June 2010.)

- Various Writers, Fortunes Made in Business. (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington. 1887.) p.358.

- Bale, G.R., Modern Iron Foundry Practice. (Manchester: The Technical Publishing Co. Ltd. 1902.) p.2.

- B.Whiteley, Iron Founding. (London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd. 1921.) p.54.

- Shaw, Ben and Edgar, James. Cores and Core Making. Foundry Trade Journal. (London. 9 November 1922.) Vol 26, no. 325. p.389.

- Brough, Bennett H (ed.), The Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute. (London: E & F.N.Spon Limited. 1899.) p.272.

- Grace’s Guide, H. Hollingdrake and Son. (https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/H._Hollingdrake_and_Son. 10th June 2022.)

- In the context of the time – especially the class system – such practices were accepted as normal and not challenged. It is no wonder, then, that the Norddeutscher Lloyd shipping company had no problem in getting about 291 passengers from the British Isles to travel to Antwerp to join one of their ships which would actually made a call in a port on the south coast of England.

This page was originally published on 12th August 2018. Latest updates were completed by 20th September 2024.