John William Hodkinson: 1900-1917 – three times a soldier

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1896 – birth to marriage

John William Hodkinson: 1896-1942 – marriage to death

John William Hodkinson: 1900-1917 – three times a soldier ... this page

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1942 – eighteen homes

The belt clasp of an officer of the 4th Volunteer Regiment of the Cheshire Regiment

- Parents: James Hodkinson and Sarah Ellen Hodkinson (remarried as Kenyon)

- Born: Monday, 20th September 1869

- Married: Saturday, 4th April 1896 (age 26 years and 6 months)

- Four children: all boys

- Died: Monday, 2nd February 1942 (age 72 years and 4 months)

John William Hodkinson in the 4th Volunteer Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment

The 4th Volunteer Battalion was in existence from 1887 to 1908 with headquarters at The Armoury, Greek Street, Stockport. The Hodkinsons moved to Stockport around the turn of the century, so it is a fair assumption that John William joined the battalion at some point between 1900 and 1908.

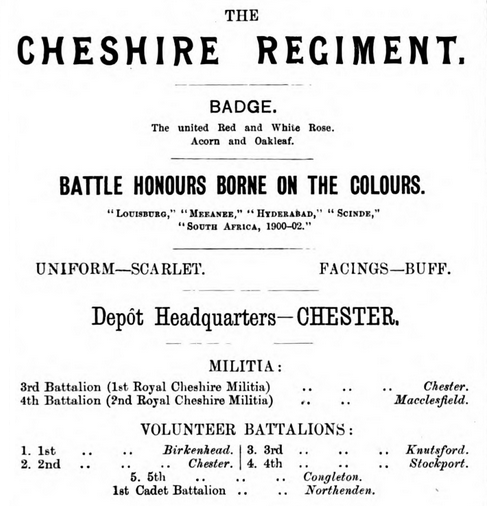

The information about the Cheshire Regiment shows five volunteer battalions, including the one at the Armoury, Stockport, where John William Hodkinson trained. (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

John William Hodkinson in the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment, from October 1914 to April 1915

John William Hodkinson was a member of the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, from October 1914 to April 1915. His army number was 12159.

John William Hodkinson re-joined the Cheshire regiment on 5th October 1914, being allocated to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion. 186 days later he was discharged on the grounds that it was unlikely that he would become an efficient solder.

Pipe-smoking, grey-eyed and brown-haired with a splendid moustache, John William was 41 years old when he attested for service in Stockport. He was slim, to the say the least, weighing 127 lbs for his height of 5 feet 7 inches – on modern height/weight charts, he is at the lower end of a healthy weight. His certificate of medical examination stated that there were no reasons under the regulations of the Army Medical Service for rejection. The standard wording on the certificate gave him a clean bill of health. "He can see at the required distance with either eye: his heart and lungs are healthy; he has the free use of his joints and limbs, and he declares that he is not subject to fits of any description."

The 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion was mobilised in August 1914 and moved to its war station in Birkenhead. Liverpool and Birkenhead were categorised together as a "Defended Port" and its garrison consisted of four Special Reserve Battalions – the "Mersey Defences" – whose role was to defend the docks, and a number of strategic positions in the Wirral and on Hilbre Island.

On the day that John William attested, he was also mobilised and made his way to Birkenhead. It is one of those coincidences that John William Hodkinson now found himself in the town where his aunts, Lucy Hodkinson (married name: Newton) and Mary Hodkinson (Wilkinson), were living at the time of his birth in 1869.

John William struggled as a soldier in the 3rd Battalion and it probably did not come as a surprise to him when he was discharged from the Army on 8th April 1915 on medical grounds. There was now just the train journey from Birkenhead to Stockport to do and then he would be re-united with his wife and three children.

However, he wasn’t finished with the army yet.

John William Hodkinson in the 331st Road Construction Company, the Royal Engineers Regiment, from May 1917 to October 1917

From Stockport to Les Brebis on the Western Front

For a number of weeks in 1917 Captain F. Corke, serving with the Royal Engineers in the Road Transportation Depot at Aldershot, was very busy doing what was needed to establish a new road construction company of which he would be officer in charge. By 21st May 1917, his work came to fruition with the formation of the 331st Road Construction Company (RCC). One of those under his command would be John William Hodkinson who had attested in Chester four days earlier, on 17th May 1917, and who was posted to Aldershot on 18th May 1917.

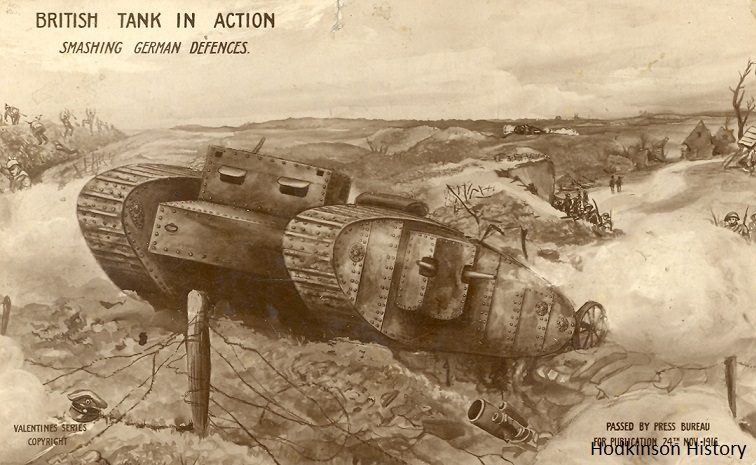

With about two weeks of training for their new roles in a road construction company, the soldiers of the 331st RCC were then ready to depart for active service overseas. John William had already been discharged from the army on medical grounds, and yet, here he was, back in the army, training for strenuous labouring work on or near the front line.

On 1st June 1917, the company could be found at Southampton, waiting to sail to Le Havre. This was the second time John William had been to Southampton: six years earlier he was on board the SS Konigin Luise, waiting for it to sail to Australia. As he left Southampton in 1911, he could not have imagined he would sail from that port a few years later to fight in a world war.

On 2nd June 1917, John William Hodkinson and the rest of his company disembarked at Le Havre and were assigned to the 1st Corps of the 1st Army. A wait of a few days followed – time to check equipment and maybe relax a little – before the company was moved by train to Les Brebis on 5th June 1917 arriving there on 7th June 1917. The distance by main rail routes was about 150 miles. Looking at the time taken to get to the destination, there is no doubt that the 331st RCC travelled by secondary rail routes with frustratingly long waits at signals and stations due to congestion. This was hardly surprising considering that the company was being moved towards the front line during the Arras offensive of 9th April to 16th June 1917, on a rail network that was under considerable strain.

It wasn’t the best of times to travel, but road repairs were essential and from 7th June 1917 onwards, John William Hodkinson and the rest of his company were fully occupied. In August 1917, one officer and 58 other ranks left Les Brebis for Petit Servins for roadwork in that area. Perhaps John William went to Petit Servins or perhaps he stayed behind in Les Brebis with the rest of the company. Whatever the case, John William was struggling with the work and it wouldn’t be too long before he would be heading back to Aldershot.

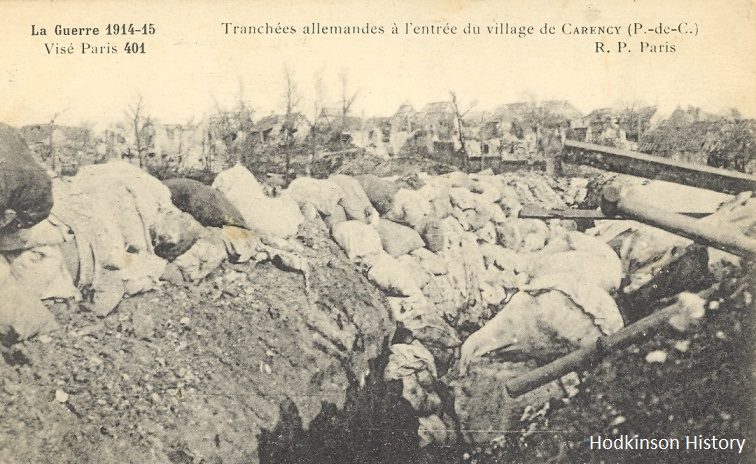

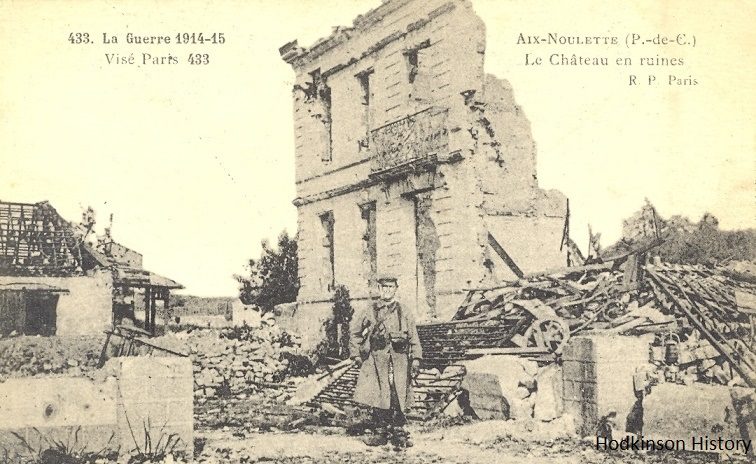

These are two more of the postcards bought by John William Hodkinson in France. The first postcard is a photograph of Carency, which is the red marker on the map. The second postcard is of Aix-Noulette and is the blue marker on the map.

Green marker = Les Brebis (nowadays Sci les Brebis).

Les Brebis is where the 331st Road Construction commenced roadworks on 7th June 1917 after making the journey from Le Havre.

Brown marker = Petit Servins.

This is where one officer and 58 other ranks of the 331st Road Construction Company moved to on 17th August 1917, leaving the rest of the company behind in Les Brebis. It is not known which group John William was with.

Blue marker = Aix Noulette.

Aix-Noulette is the location of two of the postcards on this webpage and which belonged to John William Hodkinson.

Red marker = Carency.

Carency is the location of one of the postcards on this webpage and which belonged to John William Hodkinson.

Black marker = Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery.

Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery is where John William Hodkinson's son, George Albert Hodkinson, is buried. Little did John William know that he was working just a few miles away from where his son would be killed one year later.

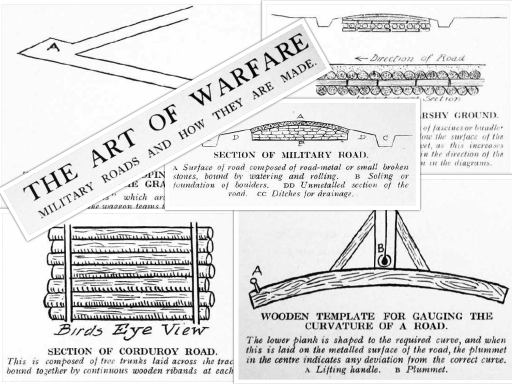

The making of temporary roads leading to the firing line is one beset with difficulty and danger, for, often enough, the work has to be carried out under artillery fire of the enemy and, when the object of the work has been discovered and the range once found, it is inevitable that the roadmakers’ handiwork will be destroyed again and again with a view to delaying transports. It is very often the case, too, that traffic commences from the moment the track is first cleared and the road has to be completed without obstructing this traffic.2

In fact, a great deal of damage was done to roads by the army's own vehicles:

... their solid rubber tyres, were most efficient road-destroying weapons... When pot-holes appeared, unless mended at once, convoys would bounce from hole to hole, like heavy pile drivers hammering on the roads. Only roads with a minimum of twelve inches of soiling and six inches of metalling well rolled down in two layers could stand up to mechanical transport, and only then if well maintained by large working parties.3

Leaving all the above aside, far more important was the possibility of death and injury inflicted by enemy aircraft, artillery and small arms fire on those working on the roads, especially when they were near the front line. It was something which John William would have been aware of and perhaps would have witnessed.

Hard labour takes its toil

John William found the work difficult and, after five months, he was posted from France to Aldershot. A medical report commented "He states that ten years ago he began to suffer with rheumatic pains all over the body which have gradually become worse. He also suffers from deafness. Says he was laid up for 6 months with 'paralysis of the brain' before enlisting." Elsewhere his medical records state that he "complains of vertigo" – doubtless this was linked to the "paralysis of the brain" that he mentioned and, in turn, may have been linked to the loss of hearing that he was experiencing. His arduous work in civilian life as a core maker, with exposure to high noise levels in harsh working environments, had taken its toll.

As he worked on road construction in France, John William would have known only too well that he was not up to the required level of fitness and it would have been disappointment, but doubtless relief as well, when, on the 7th September 1917, he made that move to the Road Transportation Depot in Aldershot. He remained in Aldershot for just over a month during which time he was assessed medically. On 10th October 1917, John William Hodkinson – three times a soldier – was discharged from the army for the last time with the reason stated as "Physically unfit." One question on the medical report asked whether his current capacity to earn a full livelihood in the general labour market was lessened. The somewhat surprising answer given was "not lessened."

It could be said it was sheer foolhardiness by John William to re-enlist in May 1917, considering what emerged in his medical report later in the year and more so in the light of his previous discharge from the army on medical grounds. It certainly does seem strange that a man who had been suffering from rheumatism and deafness before re-enlisting could get through a medical examination and could be graded medically as fit enough to serve overseas as a labourer doing hard work. Strange it might have been, but similar scenarios elsewhere relating to recruitment were not unusual. Most important of all, it probably was stoic determination combined with a desire to fight for his country that drove him to join up once again in pursuit of what he wanted to do regardless of his health, which he may well have down-played during his medical examination.

John William Hodkinson may have been disappointed to have ended his army career earlier than he wanted, but there were jobs waiting for him when he got back to Stockport. Just over a year later, the national labour market would be intensely competitive with hundreds of thousands of servicemen looking for work following the end of the Great War. At least John William avoided that.

The journey to Stockport from Aldershot would have been tedious, on a rail network stretched to the limit, with priorities given to trains carrying troops, the wounded and supplies for the front line. Still, the slow journey gave him the time to smoke his pipe many times over, read the newspaper (maybe many times over), doze, and think about his future. Maybe he looked at the postcards he had bought.

Death of John William’s eldest son, George Albert, killed in action

George Albert Hodkinson, John William’s eldest son, attested for service in December 1915 and met his end in France in August 1918, dying from wounds after an enemy attack. The news of Albert's death took some time to come through: Army records state that his father was notified on 3rd September 1918. The news hit the family hard; doubtless John William as his father, and especially as a former soldier who had been posted abroad, thought "why not me?"

Family and friends rallied around and helped the family through the dark and difficult days and weeks that followed the news of the death of George Albert. It was little consolation for his son’s death, but John William and his son were awarded the same medals after the war and the medals would have been on display next to each other in the family home – an expression of a shared army experience and of "doing their bit" for their country.

John William wasn’t a reader of The Times, but he did buy the War Graves Number, which was published on 10th November 1928. The contents include articles about graves and memorials in the different theatres of war; the war at sea; and the Royal Air Force. One section of the newspaper is entitled “The Silent World”, part of which deals with the burial of the dead in makeshift graves and their re-interment after the end of the war in dedicated war cemeteries. That would have resonated with the Hodkinson family – George was initially buried in a small cemetery, his grave marked by a wooden cross, before being moved, in August 1923, to Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, Souchez.

Medals, money and memories

Medals

Like his son, George Albert, John William was entitled to two medals. One of these was the Victory Medal, authorised in 1919, the other was the British War Medal, also authorised in 1919. The two Hodkinsons were entitled to the latter on the basis that they entered a theatre of war between 5th August 1914 and 11th November 1918.

Army records do not show when John William actually was sent his medals, but it would have been some considerable time after the end of the war: after all, George Albert’s medals were not despatched until 5th May 1920.

Like his son, George Albert, John William was entitled to two medals. One of these was the Victory Medal, authorised in 1919, the other was the British War Medal, also authorised in 1919. The two Hodkinsons were entitled to the latter on the basis that they entered a theatre of war between 5th August 1914 and 11th November 1918.

Army records do not show when John William actually was sent his medals, but it would have been some considerable time after the end of the war: after all, George Albert’s medals were not despatched until 5th May 1920.

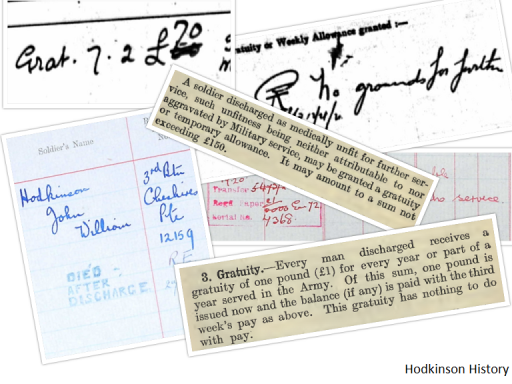

Money – gratuities

There were two categories of gratuities: war and service.

War gratuities were introduced in December 1918 as a payment to those who had served for a period of 6 months or more at home or for any length of service overseas. Service gratuities were in place before the war and eventually covered most men who served and were in addition to any monies due to them as war gratuities. John William’s service brought him a gratuity of £1 in 1920. He would have been given £3 until a clerical error was spotted! Maybe the error was made by the same person who incorrectly rubber-stamped the words "Died after discharge" beneath John William’s name on his records.

John William received no award for being discharged on medical grounds from the Royal Engineers since the conditions were pre-existing and had not been aggravated by military service. Clearly, the noise of battle and hard physical labour had not had a further impact on his health, especially his deafness and rheumatism.

Yet there was some good financial news: his Royal Engineer records show he was given a war gratuity of £50 which was then crossed out and a new amount of £70 entered. That was an adjustment that was worth having.

Memories

Eventually, the money was spent. As for the medals, over a century later, they are no longer in the family and their whereabouts are completely unknown. Other documents and souvenirs have also been lost for ever. Maybe more photographs existed, now also gone for good.

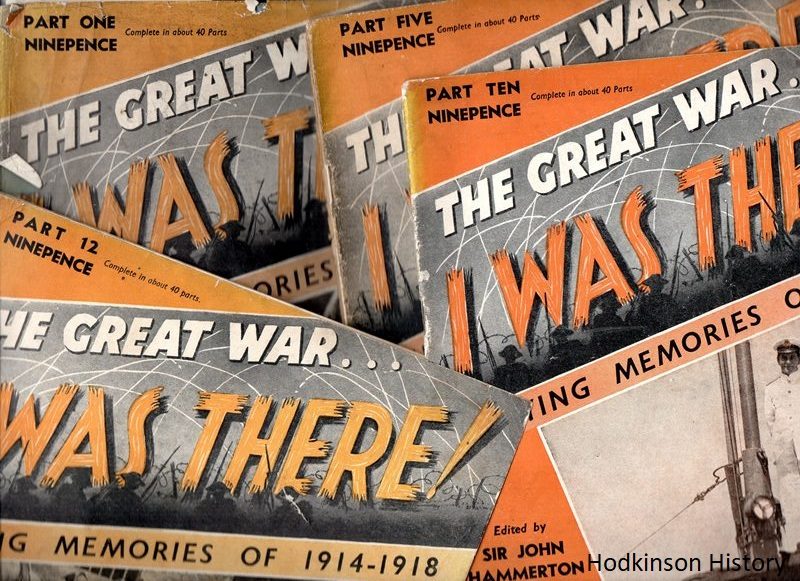

However, in finishing this page, it is worth mentioning that four issues of The Great War... I Was There, which belonged to John William, are still with the Hodkinsons. This was a magazine that had 51 editions which ran from 29 September 1938 to 19 September 1939. Like hundreds of thousands of others in the British Isles, John William could relate so well to that title and it is no wonder that he bought the magazine when it came out on Thursdays. It is quite ironic that when he read the last edition of the magazine, Britain was 19 days into World War 2. Still, John William could look back on World War 1, knowing that he had "done his bit" to the best of his ability. He could be very proud of that.

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1896 – birth to marriage

John William Hodkinson: 1896-1942 – marriage to death

John William Hodkinson: 1900-1917 – three times a soldier ... this page

John William Hodkinson: 1869-1942 – eighteen homes

Notes and sources for this page:

- Unless otherwise mentioned, this page is based on copies of birth, marriage and death certificates; census returns; and family documents and related items including photographs which are the property of Samuel Hodkinson.

- Sugden, Charles K., The Art of Warfare. Military Roads. Navy and Army Illustrated. (London: George Newnes. 1915.) p.412.

- Pritchard, H.L., Major-General, History of the Corps of Royal Engineers. (Chatham: the Institution of Royal Engineers. 1952.) Vol.5, pp.599-600.

- Hogge, J.M. and Garside, T.H., War Pensions and Allowances. (London: Hodder and Stoughton. 1918.) p.18 and p.140.

This page was originally published on 12th August 2018, with the latest update completed by 17th January 2023. There is always something to do!