1841 onwards: Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson and their shared history

The stories of siblings Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson are on three pages, as below.

- The story of the three children up to 1841 is on the first of two webpages about their parents.

- This page is about Mary's life from 1841 up to 1855 when her first child was born; Lucy's life from 1841 up to 1860 when she married for the first time; and James' life from 1841 to 1866 when he married.

- There is a separate page for each sibling for the later part of their lives, with a bit of earlier history that isn’t in the pages listed above.

Mary’s life from 1855 (when her first child was born) to her death in 1874 is here.

Lucy’s life from 1860 (when she first married) to her death in 1893 is here.

James’ life from 1866 (when he married) to his death in 1881 is here.

George and Hannah Hodkinson and their children

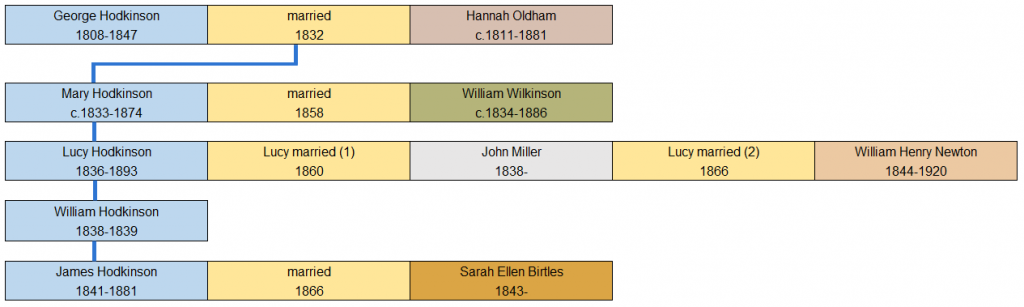

Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson can be seen in the extract below of the Hodkinson family tree, which has been repeated on some other webpages for clarity and non-hyperlinked convenience.

George and Hannah's third child, William, died when he was seven months old. There is more about him here.

1841-1866 – the Hodkinson family in Hillgate, Stockport

Following the breakdown of the marriage of George and Hannah Hodkinson in about 1841, George left the marital home. His wife and her lover, unrelated William Hodkinson, and her three surviving children, moved to Hillgate, Stockport.

Life in Hillgate, a tough area of Stockport

In 1981, Jim Hooley wrote about his childhood in Hillgate1 in the 1910s and 1920s, essentially the area where the Hodkinsons lived many decades earlier. Jim Hooley wrote of a community that was characterised by sub-standard and over-crowded housing; bustling streets and small shops; high levels of poverty, and at times, high levels of unemployment; a community where certain individuals were well known beyond their own streets and where there was a great deal of camaraderie. It is hard to imagine that any of these characteristics would have been out of place in the Hillgate that the Hodkinsons knew in the 1840s, 1850s and 1860s. Yet there was more to this portrayal. Jim Hooley mentions the violence that sometimes existed, especially on a Friday evening when public houses closed. This was also the case in Victorian Times, but it was not uncommon for such violence to be linked to tensions between the English and the Irish.

In June 1852 hostility to the Irish in Stockport reached an all-time high, resulting in one fatality and the ransacking of the town's two Catholic churches. Closer to the Hodkinsons' home was an English-Irish brawl in The Bishop Blaize public house on Lower Hillgate, stone throwing in Edward Street and the attacking of Irish homes on John Street.

Hillgate, too, was the location of a horrific murder in 1861 when two eight-year-old boys, Peter Barratt and James Bradley, badly beat two-year-old George Burgess before drowning him.

This is the Bishop Blaize2 public house on Lower Hillgate, not that far from the Hodkinsons' home on Ratcliffe Street. The drawing dates from 1852 when the pub was the scene of an English-Irish brawl, part of much wider disturbances. Note the rioters to the right of the pub. Most of those outside the pub seem unperturbed by the violent fight taking place so near to them! The photograph shows the building over 170 years later, no longer a pub, but in the advanced stages of conversion to apartments. The large black sign has faded lettering which says "Bishop Blaize". (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Members of the Hodkinson family spent up to a quarter of a century in Hillgate. As the Hodkinson children grew up, they would have become aware, as their parents were aware, of the violent undercurrents which at times surfaced in Hillgate and maybe would have personally experienced them. The Hodkinsons certainly would have developed an opinion on the tensions between the Irish and English communities. Perhaps the family joined the April 1861 thousand-strong funeral procession in Heaton Norris for the murdered two-year-old.

In 1858, the Hodkinson family size reached a peak when eleven Hodkinsons lived at 44 Ratcliffe Street, comprised of two parents (William and Hannah); three of Hannah Hodkinson's children with her first husband, George Hodkinson; four of her children with her second husband, William Hodkinson; and Hannah and William's first two grandchildren. Whatever the Hodkinsons felt about Hillgate, by about the mid-1860s, none of them lived in the area. Some of the family had died, and the rest had moved to other places in Stockport, or to other towns and cities in the UK, or to other countries.

St Thomas' – the Hodkinsons' family church in Hillgate, Stockport

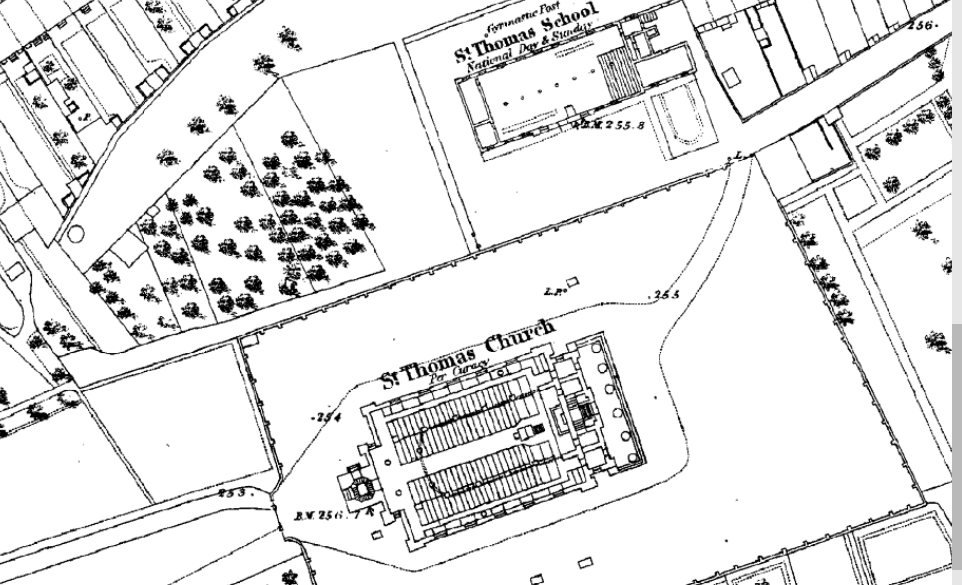

Once described as the "grandest classical church in the Manchester region"3, the Parish Church of St Thomas, in the Higher Hillgate part of Stockport, is impressive. It was built in the neoclassical style using dressed sandstone from Runcorn, had a capacity of almost 2,000, and was consecrated in September 1825 after three years of construction work.

Whilst they lived in Hillgate, St Thomas' was the family church of the Hodkinsons, with the eventual exception of Mary and James who, as young adults, joined Nonconformist churches.

It was at St Thomas' that James Hodkinson was baptised in 1842 and where, four year later, three-day-old half-sister Elizabeth Hodkinson was buried.

The graveyard closed in 1856 when it was full. When William Hodkinson, step-father of Mary, Lucy and James, died in 1858, he was buried in Stockport's Municipal Cemetery.

The education of Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson

Currently, there are no online records relating to any kind of education for Mary Hodkinson or her sister, Lucy Hodkinson. Maybe they never attended any schools at all, including Sunday schools. That would not have been surprising in an age when the education of females was second place to educating males. That is why their brother, James Hodkinson, was registered at St Mary's National School, but he appears not to have attended on a regular basis, judged by his inability to sign his marriage certificate which is a test of basic literacy. Before the advent of free education, the stark reality for so many working-class Victorian families was a choice between either paying fees to send a child to school or sending a child to work so that the child's wage could be added to the household income to make life better – even marginally – for all the family, especially in terms of paying the rent and/or experiencing hunger less often. From that point of view, education wasn't that important.

Mary, Lucy and James Hodkinson and half-brother Samuel: child labourers

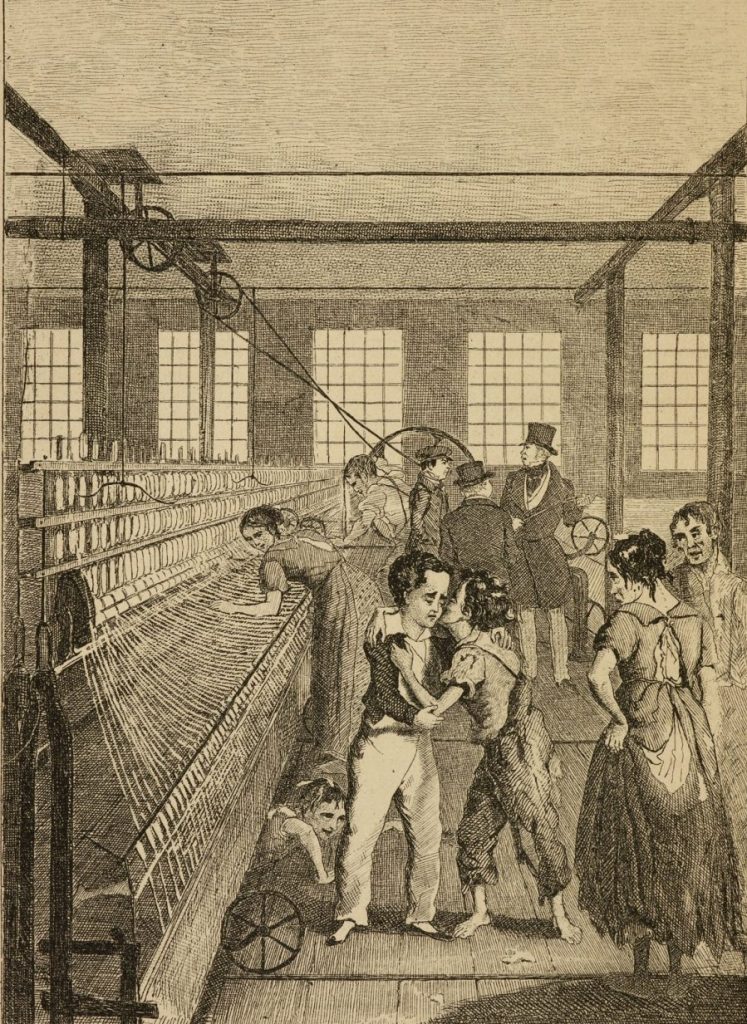

A scavenger is under the machinery and two piecers are repairing broken threads in this oft-used 1840 illustration from 'The life and adventures of Michael Armstrong, the factory boy', a novel by Frances Trollope.4 At least three Hodkinson children (Lucy, James and Samuel) worked as piecers.

James Hodkinson, the youngest of George Hodkinson's three surviving children, was nine in March 1850 and so officially able to work. Whilst that was the legal position, the reality was often different, illustrated perfectly by James' half-brother, Samuel Hodkinson, who was 7 years and 7 months old when the 1851 census took place, legally far too young to work, but the census entry states he was employed in a cotton mill. If Samuel started work before the legal age, the chances are that James and his two sisters, Mary and Lucy, did likewise.

The 1853 Factory Act brought all children of working age within the provisions of the 1850 Factory Act so that they, as with those aged 13–18, could work, at most, from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. in the summer and (with factory inspector approval) 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. in the winter. During these twelve-hour periods, breaks totalling 1½ hours were stipulated, leaving a maximum of 10½ hours for work. Saturday was a day to be looked forward to – all work was to end at 2 p.m.

The 1851 census shows that the three youngest children in the Hodkinson household – half-brother Samuel (age 7), James (10), and Lucy (15) – all worked as billy piecers which entailed leaning over spinning machines (billies) to repair broken threads. The work was repetitive, exhausting and dangerous. The three Hodkinson children – along with their older sibling, Mary – would have recognised the working environment as described by John Clynes about his work as a piecer, even though it was written much later, in 1879:

The noise was what impressed me most. Clatter, rattle, bang, the swish of thrusting levers and the crowding of hundreds of men, women and children at their work. Long rows of huge spinning-frames, with thousands of whirling spindles, slid forward several feet, paused and then slid smoothly back again, continuing the process unceasingly hour after hour while cotton became yarn and yarn changed to weaving material. Often the threads on the spindles broke as they were stretched and twisted and spun. These broken ends had to be instantly repaired; the piecer ran forward and joined them swiftly, with a deft touch that is an art of its own. I remember ... meals at which there never seemed to be enough food, dreary journeys through smoke-fouled streets, in mornings when I nodded with tiredness and in evenings when my legs trembled under me from exhaustion. 5

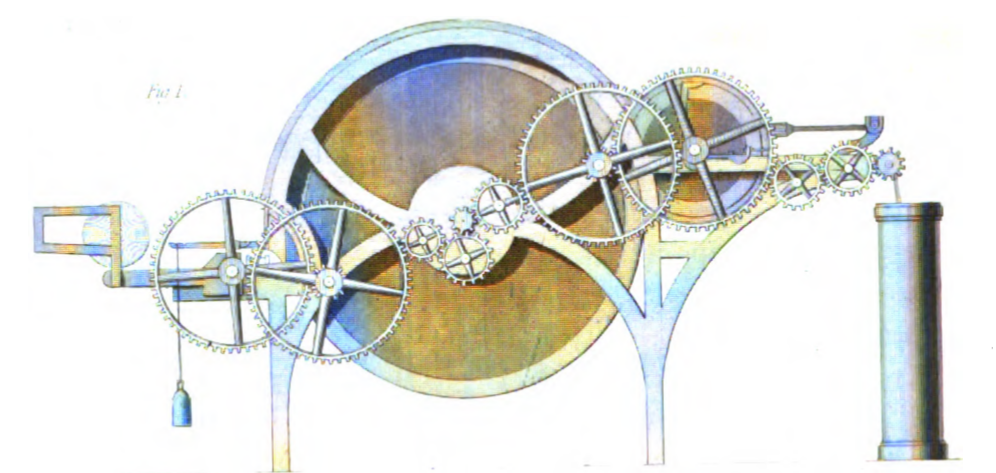

This is a machine that Mary Hodkinson and James Hodkinson, and maybe other family members, grew to know and love! This illustration dates from 18356 and shows the end elevation of a carding machine, whose workings would have been very familiar to the two siblings. Plenty of cog wheels to clean, over and over again!

It was not unusual for family members to work in the same factory and it is nice to think that, leaving aside the harshness of the working conditions, Samuel, James, Lucy and Mary worked in the same mill, maybe with other family members, maybe within sight of each other and maybe next to each other. It is quite likely they worked in, or very close, to Hillgate, where they lived.

As piecers, Samuel, James and Lucy were on low wages, with only a small number of other groups in the cotton industry, such as scavengers (children who picked up the loose cotton from under the machinery) earning less. Despite their low earnings, the total of these three wages and that of the oldest child, seventeen-year-old Mary Hodkinson, who worked as a power loom tenter, would have been an important contribution to the Hodkinson household budget. Typically, the mother of a working-class Victorian family would take those earnings and add them to her earnings, if any. The father's wages would also become part of the combined household income, but only after he had top-sliced it for beer money. On that basis, Mary, Lucy, James and Samuel surrendered their wages to their mother, Hannah Hodkinson. She added in what was left of her husband's wages.

There were a small number of fathers who did not drink, but it is highly unlikely that (step-) father William Hodkinson was one of them. After all, he had spent almost 26 years in the British Army, with many years in New South Wales and India, and the combination of army life, hot countries and beer as a standard military drink doubtless meant that, once back in Stockport, he would have carried on with his drinking habits.

From William Hodkinson's point of view, having a public house, the Queen, just a few doors away from his own home was a bonus. From the point of view of other members of the family – and perhaps they never thought this, let alone voiced it – William Hodkinson's drinking habits effectively reduced the amount of money available to the rest of the family for essentials.

The census of 1851 shows that only the working children in the Hodkinson household were piecers; typically, it was a job that children did, especially since adult piecer earnings were also low. Consequently, adults would look for better paid work, even if the difference in pay rates was not huge. This was the case with James Hodkinson who was employed as a labourer in a cardroom by the time of the 1861 census. By then, Lucy was a cotton reeler, operating a machine that fed yarn onto bobbins.

Hodkinsons' homes in Hillgate, Stockport from 1841 to about 1866

The Hodkinsons lived in Cheadle, then Rowcroft Smithy and Heaton Norris, before moving to Hillgate, where various Hodkinsons lived from about 1841 to about 1866.

These are the known dates and locations of the homes of Hodkinsons in Hillgate:

1842-1843: Union Street;

1846-1847: 44 Mottram Street; and

1850-1866: 44 Ratcliffe Street.

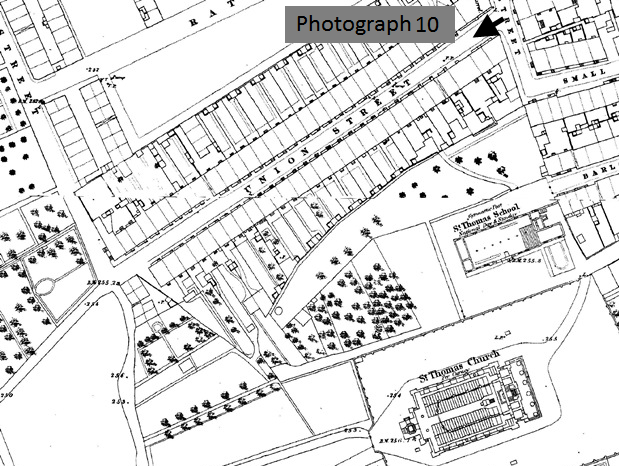

Union Street, Hillgate, Stockport

The Hodkinsons lived on Union Street from about 1841 to at least 1843. The number of the house is not known.

Photograph 10. This is a 1960s view of Union Street, looking towards Wellington Road South. The Hodkinsons lived somewhere along here in the early 1840s. In 1861, Lucy Miller (Lucy Hodkinson) lived at number 43 as a lodger. (Photograph: acknowledgement to Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council Image Archive.7)

At some point soon after 1841, George left the family home following the break-up of his marriage to Hannah Hodkinson. Those living in Union Street reflected the new Hodkinson family structure.

The family home on Union Street was occupied by:

- Hannah Hodkinson (born about 1811), mother;

- William Hodkinson (born 1798), future second husband of Hannah Hodkinson;

- Mary Hodkinson (born 1833), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- Lucy Hodkinson (born 1836), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- James Hodkinson (born 1841), son of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson; and

- Samuel Hodkinson (born 1843), son of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson.

By 1846, the Hodkinsons had moved to Mottram Street. Whether they moved directly from Union Street to Mottram Street is not known; maybe they lived somewhere else in the meantime.

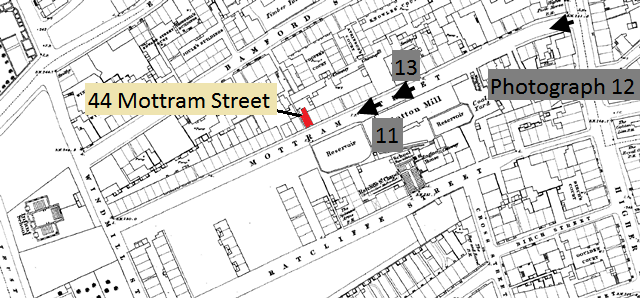

44 Mottram Street, Hillgate, Stockport

The Hodkinsons lived at 44 Mottram Street from about 1846 to at least 1847.

For some or all of the time, the family home was occupied by:

- Hannah Hodkinson (born about 1811), mother;

- William Hodkinson (born 1798), future second husband of Hannah Hodkinson;

- Mary Hodkinson (born 1833), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- Lucy Hodkinson (born 1836), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- James Hodkinson (born 1841), son of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- Samuel Hodkinson (born 1843), son of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson;

- Elizabeth Hodkinson (born 1846 but died after three days), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson; and

- Ellen Hodkinson (born 1847), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson.

This is an extract from an Ordnance Survey map with the surveying date given as 1849. The photograph numbers relate to images below.

Photograph 11. This 1960s view of part of Mottram Street is taken from its junction with Police Street which ran through to Bamford Street. 44 Mottram Street was two doors to the right of the Mission Church of St. John's which was prominent in the row of terraced houses on the right-hand side of the street. (Photograph: acknowledgements to Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council Image Archive.8)

Photograph 12. This is a view of Mottram Street looking towards Mottram Towers from Hillgate on a cold winter's day with a low strong sun. On the right are a number of buildings which date from the time when the Hodkinsons lived on this street. It is more than likely that William Hodkinson and James Hodkinson frequented the building on the right at the end of the street, which was once The Higher Pack Horse public house. On the left of the photograph is the Salvation Army's 1894 building, which presented a clear challenge to the then existing public house opposite. Both buildings, however, have shared a common fate – conversion to apartments. (Photographs: Samuel Hodkinson.)

Photograph 13. The present-day route of Mottram Street differs from the pre-1960s alignment which ran more or less in a straight line from Hillgate to Wellington Road South. Part of the course of the street was to the left of the large wooden structure which is at the back of Mottram Towers. As for the site of 44 Mottram Street, the Hodkinsons' home, it is beneath the brick building which runs alongside the tower block. (Photograph: Samuel Hodkinson.)

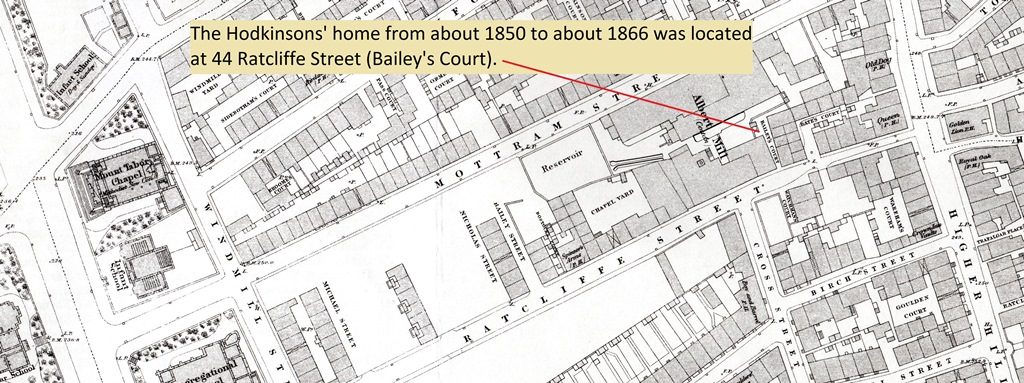

44 Ratcliffe Street (Bailey's Court), Hillgate, Stockport

The Hodkinsons' home at 44 Ratcliffe Street was in Bailey's Court.9 The map has a revision date of 1873. Only two short sections of Ratcliffe Street remain; the first photograph shows one of them, as viewed from Hillgate. Its width was adjusted in recent years to accommodate the new buildings on both sides. On the corner to the right was a public house – the Queen – which the adult male Hodkinsons would have frequented when they lived just a short distance away. The second photograph shows the location of the entrance to Bailey’s Court – the big tree is, give or take a metre or two, where the bottom of the red line is on the map. (Photographs: Samuel Hodkinson.)

The Hodkinson family size reached a peak in 1858 when eleven lived in the home. They were:

- Hannah Hodkinson (born about 1811), mother;

- William Hodkinson (born 1798), second husband of Hannah Hodkinson;

- Mary Hodkinson (born 1833), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- Lucy Hodkinson (born 1836), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- James Hodkinson (born 1841), son of Hannah Hodkinson and George Hodkinson;

- Samuel Hodkinson (born 1843), son of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson;

- Ellen Hodkinson (born 1847), daughter of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson;

- William Hodkinson (born 1850), son of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson; and

- John Hodkinson (born 1852), son of Hannah Hodkinson and William Hodkinson.

It is probable that Mary Hodkinson's first two children, born before marriage, also lived at the same address until 1858:

- John William Hodkinson (born 1855), son of Mary Hodkinson and William Wilkinson;

and - Mary Wilkinson (born 1857), daughter of Mary Hodkinson and William Wilkinson.

A farewell to Stockport

During the twenty-five years that some or all the Hodkinsons listed above lived in Stockport, there were many local and national initiatives which helped to improve the lives of the inhabitants of the town. For example, standpipes and water carriers were being replaced by indoor taps; in 1853 mill owners had to reduce smoke emissions; in 1854 sewers began to be laid in a number of areas including Higher Hillgate; and the first public baths were opened in 1858. In that year, the town's first public park, Vernon Park, was also officially opened before an estimated crowd of over 30,000 which may well have included some of the Hodkinson family.

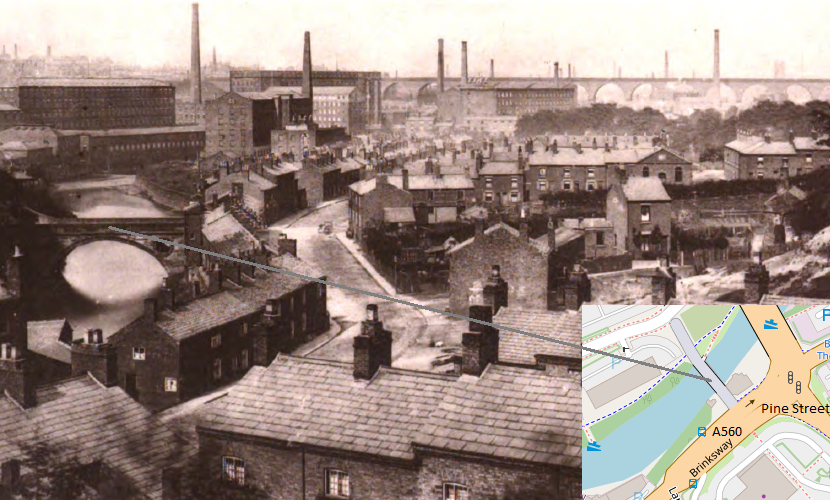

Railways were changing the landscape of the Borough of Stockport. When the first train ran across the Manchester and Birmingham Railway Company's landmark viaduct across the River Mersey in 1841, the three Hodkinson children were aged seven, five and one. By the time they were adults, the Borough was well on the way to being criss-crossed by a network of lines. In this process of railway expansion, the Hope and Anchor public house at the bottom of Bury Street, which was most likely frequented by the children's father when he lived in Heaton Norris, was demolished.

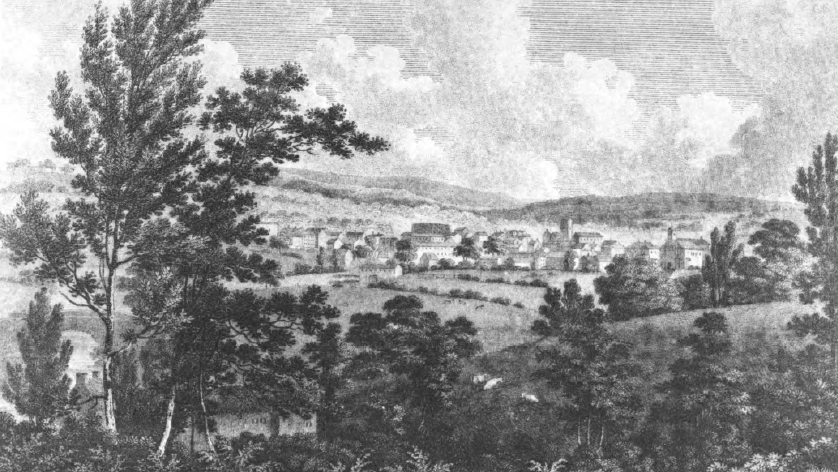

The images above and below are of views of Stockport, both from Brinksway Bank.10 The drawing is dated 1793 and the photograph is dated 1876. What a difference eighty or so years can make!

Despite these and other developments, conditions in Stockport for the majority of the inhabitants remained harsh. Death rates in Stockport and Manchester in 1869 were higher than any other town in the country.11 In the 1850s the town council rejected a proposal to restrict the use of cellars as dwellings.12 Social unrest was not uncommon. In 1842 a strike in Stockport collapsed, with cavalry used to maintain order. Ten years later, the riots of 1852 were indicative of the intra-communal tensions between the Irish and English, which were often just below the surface of everyday life. Part of the tension was fuelled by the growth in the Irish population, matched in roughly the same numbers by other workers who left the town for a better life elsewhere.

Above all, during the Hodkinsons' time in Stockport, the town did not grow economically. The family would have been hit hard by the economic depression which ended in 1843 and, although there was a subsequent revival, the Hodkinsons of working age were again to live through tough times. The worst was from 1861-1865 when a severe economic downturn had a devastating impact on employment in the Borough. This prompted the Hodkinsons still living in Hillgate to do what many other individuals and families had already done – to move elsewhere in Stockport or further afield to get work, either in its own right, or because better pay was to be had.

Where to go next?

Well, there is the main menu at the top of the page for all the Hodkinsons researched so far. However, here is a repeat of where to find the stories of siblings Mary Hodkinson, Lucy Hodkinson and James Hodkinson.

The story of the three children up to 1841 is on the first of two webpages about their parents.

The information on this current page deals with the next stages of their lives from 1841.

Finally, there is a separate page for each sibling, with a bit of earlier history that isn’t in the pages listed above, which covers the dates as follows:

Mary’s life from 1855 (when her first child was born) to her death in 1874 is here.

Lucy’s life from 1860 (when she first married) to her death in 1893 is here.

James’ life from 1866 (when he married) to his death in 1881 is here.

Notes and sources for this page:

- Jim Hooley, A Hillgate Childhood. (http://www.snoringunicorn.co.uk/hillgate1.htm. 10 August 2013.)

- The Illustrated London News, The Riot At Stockport. (London: 10 July 1852.) p.28.

- Peter Arrowsmith, Stockport, A History. (Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Council, 1997.) p.209.

- Frances Trollope, Life and adventures of Michael Armstrong, the factory boy. (London: Colburn, 1840.) Scanned from illustration facing p.82.

- John Clynes, quoted in Piecers in the Textile Industry. (http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/IRpiecers.htm. 15 August 2013.)

- Edward Baines, History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain. (London: H. Fisher, R. Fisher and P. Jackson, 1835.) Scanned from the illustration following p.179.

- Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, Stockport Image Archive. (http://www.stockport.gov.uk/services/leisureculture/libraries/libraryonline/stockportimagearchive. 10 May 2013.) Image 791.

- Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, Stockport Image Archive. (http://www.stockport.gov.uk/services/leisureculture/libraries/libraryonline/stockportimagearchive. 10 May 2013.) Image 648.

- The censuses of 1851 and 1861 state the Hodkinsons lived at 44 Ratcliffe Street. The numbering of the street started at the Hillgate end and, in the early years of building, courts and side streets that came off Ratcliffe Street were numbered as though they were on Ratcliffe Street. This was not a logical system, especially when new side streets did not fit easily into the numbering sequence. However, the 1871 census shows that the street’s numbering system had been reorganised and courts and side streets now had their own numbers against their own names. In turn this had an impact on Ratcliffe Street itself where most numbers were changed.

- Henry Heginbotham, Stockport: Ancient and Modern. (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. 1882.) Vol. I. Illustrations: frontispiece and between p.viii and p.ix.

- Peter Arrowsmith, Stockport, A History. (Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Council, 1997.) p.238.

- Peter Arrowsmith, Stockport, A History. (Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Council, 1997.) p.240.

This page was originally published on 12th August 2014 with its format totally changed by 5th May 2023. Latest updates were made on 14th May 2024.